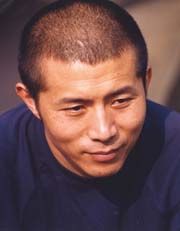

The Chinese novelist Bi Feiyu has been awarded in recent months the two most prestigious literary awards in Asia and particularly the Mao Dun prize, the Chinese “Goncourt”. In Paris for a few days, on the occasion of the release of his latest novel “The Blind” (1), we were able to meet him: a bon vivant, a good craftsman, happy in today’s China.

The Chinese novelist Bi Feiyu has been awarded in recent months the two most prestigious literary awards in Asia and particularly the Mao Dun prize, the Chinese “Goncourt”. In Paris for a few days, on the occasion of the release of his latest novel “The Blind” (1), we were able to meet him: a bon vivant, a good craftsman, happy in today’s China.

A reputation that is growing rapidly:

Well supported by his French publisher, Philippe Picquier, which published five of his books, he began to be known in the Anglophone world, where two of his novels have been translated, including “Three Sisters” which won the Man Asia prize.

We were able a few months ago to underline the importance for him of power and domination, he also describes the suffering created by the historical upheavals of his country but refuses the label of novelist of feminine psychology given to him by American critics.

He is 47 years old, his childhood was somewhat wandering because his father, condemned as a “rightist”, was sent to work in the countryside. Ecole Normale, professor and journalist, he settled in Nanjing where he was editor of the literary magazine of the Writers Union.

The first two publications in France: “The Moon opera” and from the publisher Actes Sud “Cotton candy on a rainy day” were very well received. The three novels that followed, including “Three Sisters”, have shown a real talent but also some limitations.

His latest book, “Blind” was a great success among the Chinese public, long before the Mao Dun Prize, and is winning support.

Their world is not ours:

Fifteen blind practice in a medical office, massage for pain relief and cure. Bi Feiyu leads us into an unknown world where the blind live a very repetitive working life but where the characters and relationships are very different.

We are far from a sociological study but you learn the differences between a man born blind and a late blind. We know the importance for the blind of hearing and smell, the role of touch for massage but also for the contacts between them. The author points out several elements of their character: patience, superstition and fatalism (“how to stand up to fate? The safest, most effective attitude is in one word: accept”).

“The omnipotent fires of the looks of the valid”:

But the key is there, “they must rely on the eyes of the valid to judge and act. Ultimately, their own social ties are eventually integrated into the sphere of the valid. They do not even know that their own judgments are actually those of others. “

Furthermore, “the blind … live under the eye of those who see, and via the opinions they collect, they get some idea of the physical outlook of each of them ….” The head of the clinic, falls in love with one of his employees when he hears customers praise her great beauty …

The story of the characters, their personality, their relationships are analized in depth. The tone is realistic, but it is not to expose the situation of the blind even though, we learn that they receive from the state a monthly allowance of 10 euros and that the employment contracts and social coverage are virtually non existing.

The story of the characters, their personality, their relationships are analized in depth. The tone is realistic, but it is not to expose the situation of the blind even though, we learn that they receive from the state a monthly allowance of 10 euros and that the employment contracts and social coverage are virtually non existing.

The inclusion of this group in the city of Nanjing in present day China, is not the objective of the author who is satisfied with a plot that serves mainly to develop a collection of portraits. Engaging characters that allow the author to take a very specific look on their environment.

With the help of the translator of the book, Emmanuelle Péchenart, we had with Bi Feiyu, a long conversation. The topics concerning his work, colleagues, publishers, agents, translators, literary awards, the Writers’ Union, internet, life in Nanking, are published on my blog www.mychinesebooks.com

What is the origin of your book?

At the Ecole Normale, I taught students who were destined to become teachers for the blind. I was able to interact with students of my students, while it is usually difficult to live with the blind and obtain their trust. I met them, talked to them but I did not make a systematic investigation.

You mention that I do not speak much of the condition of the blind in China, it’s true and people have little regard for them, but I would have written another novel if I had wanted to address this problem. My topic was really the description of a society for the blind because it has never been done … and you have to know that in China, the book has already been published in Braille.

We sometimes feel that your novel is primarily a collection of portraits …

It is true that the structure is simple, it is that blind people do not live like us, life is dispersed. But within these portraits, I have established links between the different characters, which was rather difficult, but fortunately I am now quite experienced as a writer!

Is this group of blind people a way to critique the society of the non blind, what Lianke Yan has achieved with his company of handicapped (2)?

No, it was not my project, it would not be correct for the blind. For me, this novel is to represent the blind as a society … a society of blind and of non blind, it’s actually the same. The social criticism is present in some of my other books, “Three Sisters”, “The Plain”. As a writer, I think I have a political responsibility, but that does not mean that all my texts must have a political content. I think that the way to describe the fate of a person and the relationships between characters are more important than politics as such.

You say that”The Plain” is a novel about the Cultural Revolution …

I think I make a fairly broad description of the Cultural Revolution; often in the novels of this period, the subject is approached from the perspective of the fight against a person or class struggle in a particular area. I think it’s pretty superficial. I wanted to show how the Cultural Revolution interfered in family relationships, birth, funerals, sex …

Apart from some difficulties during the release of “Cotton candy on a rainy day,” have you had problems with censorship?

I do not accept cuts, but there are authors who talk a lot about pressures they have suffered for their work, I do not want to talk about it continuously. It is true that there are pressures on writers today. But the problem is mainly that fewer and fewer people are interested in literature. This is true for the readers but also for the government which is particularly interested in media, Internet and film. To speak frankly, there are pressures but not that important …

Bertrand Mialaret

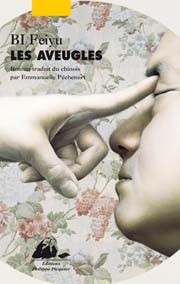

(1) Bi Feiyu, “Les Aveugles”, translated by Emmanuelle Péchenart; Editions Philippe Picquier, 2011, 460 pages, 22 euros. (also known as « Massage”)

(2) Yan Lianke, ” Bons baisers de Lenine”, translated by Sylvie Gentil. P. Picquier 2009.