Keris Mas (1922-1992) is a major writer of Malay literature. Militant in the 1950s against British colonialism and in favor of “art for the people”, he will try to decrease obstacles against progress in society while justifying in his four novels and sixty short stories the necessary compromise between tradition and modernity.

Keris Mas (1922-1992) is a major writer of Malay literature. Militant in the 1950s against British colonialism and in favor of “art for the people”, he will try to decrease obstacles against progress in society while justifying in his four novels and sixty short stories the necessary compromise between tradition and modernity.

Two of his novels have been translated into French by Brigitte Bresson: colonial Malaysia with “The Jungle of Hope” (1-4), and the 1980 period in “The great trader of Kuala Lumpur” (2). Twenty short stories (1946 to 1960) are available in English, “Blood and Tears“, translated by Harry Aveling (3).

– Rice and rubber:

In “The jungle of Hope“, rice farming, as in many Malay villages is a symbol of tradition while rubber plantations (and later palm oil) are a sign of adaptation to the modern world . In this novel, two brothers, Kia and Zaidi, embody this conflict. The author mocks inertia: some Malays “spent their entire days at the cafe, chatting and playing cards. There was enough rice in their loft, there was enough shoots to harvest in the forest and there were fish in the swamps. That was enough for them. They made no extra effort. Their fate was already determined anyway “(p.47).

Money and education (especially for girls) have a marginal role: Kia does not want his son Karim to continue his education in English schools. “He did not want his son to become one of those Malays who lived like water hyacinth, floating on the surface without buds or roots” (p. 60).

Whites develop the country to enrich themselves. Malays do not want to work for others because they are too proud. But the colonial system brought foreign workers, Indians and mostly Chinese. Tensions between Malays and Chinese are developing; Bentong in Pahang province, hometown of the author, is gradually becoming a Chinese city.

Malays create new villages and are clearing the jungle to continue their traditional way of life. But only the aborigines, mostly despised, are truly free. Malays use them to cut down the big trees but they have to wait their goodwill and not give them orders.

Life is difficult in these new villages in the jungle: clearing is tiresome, sanitary conditions are primitive and animal attacks (elephants, wild boars, monkeys) happen quite often. The shaman claims to defend the villagers and his prestige is sometimes greater than that of the Imam; Zaidi deplores these anti-Islamic rituals and idolatry that are shared by many villagers.

Life is difficult in these new villages in the jungle: clearing is tiresome, sanitary conditions are primitive and animal attacks (elephants, wild boars, monkeys) happen quite often. The shaman claims to defend the villagers and his prestige is sometimes greater than that of the Imam; Zaidi deplores these anti-Islamic rituals and idolatry that are shared by many villagers.

But to progress, one must understand the changes taking place. Latex prices may fall sharply, the shops owned by Zaidi will then suffer; but it is also the time to buy land or rubber plantations and Kia finally will be convinced to do so. He accepted this compromise but will not give in on the future of his daughter and of Karim who will stay in the village.

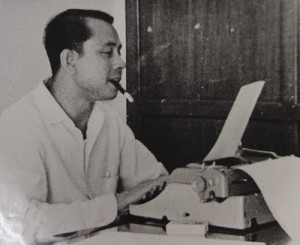

– Keris Mas, an activist, journalist, writer:

He was born in 1922 near Bentong and is educated in his village, then in a religious college in Medan (Sumatra), where he learned Arabic. In 1945, he joined the National Party and develops a Malay opposition to the British in his native region. In 1947 in Singapore, he worked as a journalist and wrote his first short stories.

With others, he creates the movement Writers 1950 (Asas50) and “art for the people”. We must develop the Malay society by removing obstacles and elites linked to colonialism. The Malay language and nationalism are promoted. In 1956, he launched the Institute of language and literature (Dawan Bahasa dan Pustaka) and worked there for twenty years. In 1981 supreme honor, he was the first to receive the title of “National Writer”.

– Muhammad, a Malay entrepreneur:

In “The great trader of Kuala Lumpur” Keris Mas praises the qualities of Muhammad because ” usually if they knew how to manage the business, the Malays could not do long-term plans; if they knew how to manage and plan, they could not implement their ideas” (p.13)

The Malays must not leave industrial sectors to the Whites and Chinese. “The Malays have to invest again in the tin business. But we need knowledge and experience of the business world” (p.213). For tin mines, one must control the land and have adequate financial resources.

Muhammad is Datuk Tan’s partner; the mining company is not an “Ali Baba Company” like many others where the Malays are only figureheads. He manages and controls it. The book is set in the 1980s, era of the development by Prime Minister Mahathir of the policy of economic control by the Malays (NEP, New Economic Policy) which generated strong tensions with Chinese investors and foreign companies.

Muhammad is Datuk Tan’s partner; the mining company is not an “Ali Baba Company” like many others where the Malays are only figureheads. He manages and controls it. The book is set in the 1980s, era of the development by Prime Minister Mahathir of the policy of economic control by the Malays (NEP, New Economic Policy) which generated strong tensions with Chinese investors and foreign companies.

The book hardly mentions this situation; cooperation is good between Muhammad and Datuk Tan. They have more difficulties with their own children: Robert, an engineer in England, is mainly interested in religions and the other, Rahim, refuses the type of development advocated by his father and this Western individualism that leads to a materialist society.

Muhammad will do everything to expand all the properties he owns with his brother in order to start mining operations: a visit by the Sultan is organized, an agreement is reached with the member of the area, intermediaries are used and even some hooligans who are not properly controled.

Eventually a compromise will be reached. Muhammad will have to accept a land given with a Wakaf status; it must be for a religious purpose and will be used to build a mosque, offices and dormitories for employees. Robert and Rahim will then agree to work for the mining company and will settle on the spot. “Religion, customs and lifestyle of the Malays should not and cannot disappear” (p.398).

These two novels are read with pleasure in a pleasant translation by Brigitte Bresson. The characters are not schematic and do not illustrate the views of the author; they are complex and endearing. This confrontation of colonial Malaysia and the 1980 period is very interesting; the author controls his narrative and we follow the novel with pleasure even if we know that there will be a final compromise.

– Short stories, highly political:

Keris Mas is famous for his short stories. The first (1946-1948) are almost political leaflets or romance without much interest. But already (Not Because of me, 1948), he criticized the village chiefs, Imams and rich Malays: “In big towns, people are open about their dishonesty, while in the country, they make use of all lots of fancy names, money, status and religion, to achieve their ends “(p.40).

He regrets the load of tradition, too many children who can not be raised properly (Too many children, 1952). Devouts who are only fasting in public are criticized (The Back Room, 1952). He shows that the obsession to have a son can destroy a family (For want of a son, 1952).

A short story from 1956 (A row of shop houses in our village), recalls the anti-British underground and points out that the Chinese and Malays then join this resistance movement in the jungle while in fact it was mainly Chinese and lead by the communists.

After independence in 1957, he mocks British officials remained in place (They do not understand) (3.5); “It’s to people like me, like us, to all expatriates, that have the task of ensuring that independence will not drift them away from us who are their teachers and their former protectors “.

The political career breaks marriages (Breakdown, 1960): Hashim, elected, will enjoy the benefits of his job and his marriage with Hasnah will not mean anything.

Some short stories are of high quality. Short texts, tense, sometimes with an unexpected fall. The author remains outside and avoids over moralizing comments. He is cautious, relations between Malays and Chinese are not touched on, although the book ends in 1960, well before the 1969 race riots.

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Keris Mas, “The jungle of Hope”, translated by Brigitte F. Bresson. Les Indes Savantes, 260 pages, 2011.

(2) Keris Mas, “The Great Trader of Kuala Lumpur”, translated from Malay by Brigitte F. Bresson. Les Indes Savantes, 400 pages, 2012.

(3) Keris Mas, “Blood and Tears”, translated from Malay by Harry Aveling. Oxford University Press, 160 pages, 1984.

(4) Keris Mas, “Jungle of Hope” published by ITNM, 315 pages, 2000.

(5) “Baboon and other short stories from Malaysia,” an outstanding publication in French of Editions Olizane, 1991. Keris Mas, page 73-88, “They do not understand”, translated by Denys Lombard.