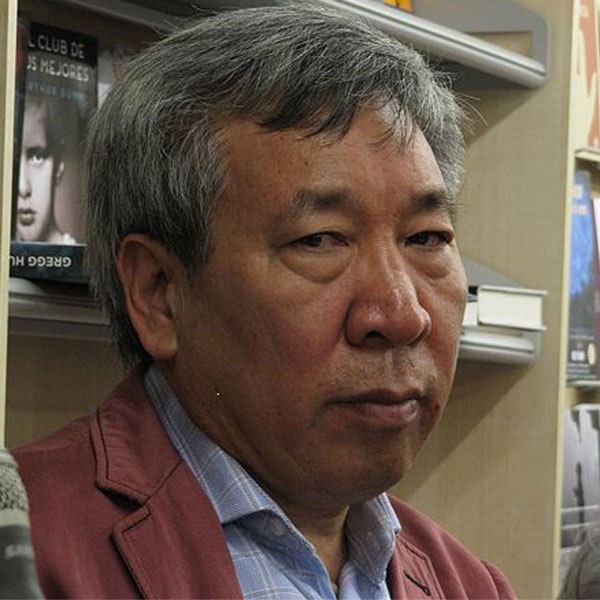

Yan Lianke is one of the most important contemporary novelists, who could become a Nobel prize winner. A major work, “The Death of the Sun” (La mort du soleil) (1) has just been published by Editions Philippe Picquier, which has done a considerable amount of work, with ten publications, to make Yan Lianke’s novels better known.

The book has been translated into French by Brigitte Guilbaud, whose translations of several of the author’s novels have been appreciated, specially “Les jours, les mois, les années” (2); she is a novelist, teacher and currently Inspector for Chinese with the French Ministry of Education.

Like the author and the publisher, at the opening of the novel, she pays tribute to Sylvie Gentil, who died nearly two years ago and who translated five books by Yan Lianke, including another masterpiece, “The Four Books” (3).

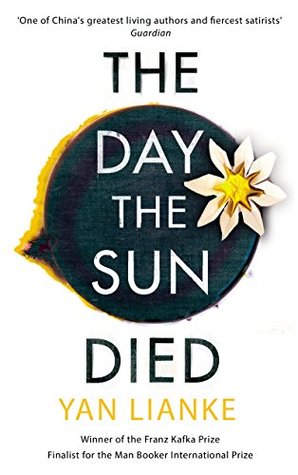

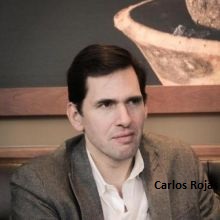

Translations into English have multiplied under the impetus of Carlos Rojas, a professor at Duke University, who translated five of his novels, including “The Day the Sun Died” (4) in 2018, which within a few months received flattering appreciations throughout the world.

This novel was published in Taiwan in 2015 and, like the vast majority of Yan Lianke’s works, is not allowed in China. The book was crowned in 2016 by the prestigious prize awarded every two years to a novel written in Chinese by an international jury in Hong Kong (5).

– A tragic night:

This is not a historical portrait as in other of his books or a realistic or mythical narrative, even if death everywhere reminds us of the Cultural Revolution. In the small town of Gaotian, in the centre of China, a fifteen-year-old boy, Li Niannian, will tell us in eleven chapters about this incredible night. Niannian is neither particularly bright nor educated, but he has a sense of family and responsibility.

The first cases of somnambulism occur at nightfall, the first deaths too concerning elders who drown in the canal; often peasants who want to continue harvesting their wheat. “So that was sleepwalking. A wild bird that entered a man’s mind and made him disorderly. His thoughts, he makes them come true in his dreams. What he must not do, he does precisely” (p.34).

– A family living on death:

Likewise, Niannian’s sleeping mother continues her paper cut-outs for the funeral. The family operates a store, “A New World”, which sells funeral articles and lives comfortably on them. Funerals are the subject of violent controversy because cremation is now mandatory, something this rural society most often refuses. The rituals surrounding death, the coffin, the grave, are essential elements of this civilization.

Cremation must be imposed even if traditional funerals are impossible in the cities due to lack of space in cemeteries. It is a question of conserving arable lands or transforming cemeteries into agricultural areas.

In Zhoukou in Henan (Yan Lianke’s province), corpses are to be moved after free cremation. In Jiangxi province, bonuses are given to families who hand over the coffin to the funeral service.

In our novel, Niannian’s father, Li Tianbo, systematically informed against families who proceeded to burials and then received 400 yuan from his wife’s brother who ran the crematorium. He would by force retrieve the coffins and eventually blow up the graves. The ashes of the deceased were given to the families but the oil from the bodies was kept by Li Tianbao in barrels.

– Yan Lianke, a character in the novel:

The novelist is very close to Niannian who reads his books but doesn’t understand them and can’t quote them correctly. Yan Lianke is a celebrity of Gaotian but the writer is very concerned about his inability to write new stories; he gets old, he withdraws into himself. In his sleepwalking fits, inspiration invades him but abandons him as soon as he wakes up; this extraordinary night will provide him with a subject.

“Because of sleepwalking, one man after another died. Not all of them threw themselves into the river: some stole, looted, were stabbed. It seemed as if the main road was swarming with the sound of bandits’ footsteps. You also had the impression that you couldn’t hear anything” (p.175).

The arrival of villagers from the surrounding area accelerated the looting. These peasants were frustrated of not being able to become city dwellers and went to “help themselves” in the shops of the village. The local authorities do nothing but banquet and donning mandarin costumes forgotten by a theatre company and pretending to relive the Taiping kingdom.

Sleepwalking can lead to making amends. Li Tianbo wants to make amends and admits that it was he who informed against the forbidden funerals; similarly, a neighbour admits to having poisoned her husband. Li Tianbo and his son try to limit sleepwalking by providing neighbours and friends with strong tea to keep them awake; they are the ones who will ultimately save the town and allow the sun to shine again.

-Political criticism and entering the secrets of human soul:

Several interviews with Yan Lianke allow the author to clarify his thoughts (6). This somnambulism refers to Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream”, even if it indicates that “the personal dream is more important than the national dream”. “The country is like a boat floating on the sea and you have no idea where it is going to float next. This is what makes Chinese people most insecure. Just like in the story, all the dreamers are very clear what they want to do but when they wake up, they do not know” (6b). “Because information is so tightly controlled, generations of Chinese have been dreamwalking through life without realizing it” (7).

But at the same time, the novelist says it is a plunge into the depths of the human soul, into its darkness. Sleepwalking frees us from conventions and reveals true personalities.

Just as Lu Xun in the preface to “Cries” compared society to an iron house and tried to use literature to awaken his fellow citizens, so Yan Lianke hopes that “his writing, in other words, is like the blind man with the flashlight who shines his light into the darkness to help others glimpse their goal and destination” (Preface by Carlos Rojas).

– A great literary talent:

Only one night, eleven chapters and sections that refer to the traditional time tracking system (geng-dian). A slow progression; it is the logic of this night that keeps the reader awake without the numerous events being organized to revive his interest.

Few characters, the narration is done by Niannian and this intervention of a teenager makes these unheard of episodes more acceptable. It is one of the writer’s talents in many of his books, to make us share incredible, absurd or grotesque events by letting us believe that it is a normal course of events. Myth, realism or rather mythorealism, the reality in China is so unlikely that it often defies acceptance.

This night is not treated like a fable; the novel is alive, the descriptions, the dialogues, the events catch the reader’s eye, but the style sometimes gives the impression that the narration floats like a sleepwalker. In my opinion, from a literary point of view, this is Yan Lianke’s most beautiful book.

In a few weeks, “Three Brothers, memories of my family” will be published; an autobiographical text translated by Carlos Rojas (8), a large part of which has already been published by P. Picquier in 2010 (“Songeant à mon père” (9)). The author recounts his youth in his village in the province of Henan, the poverty of his parents and uncles and his desire to become a writer.

He will certainly surprise us again. He tells us (7) about a new novel “Heart Sutra” devoted to religion. He is not a believer but religion interests him because “in China, the development of religion is the best lens through which to view the health of a society…Every religion, when it was imported to China, is secularized…What is absent in Chinese civilization, what we’ve always lacked, is a sense of the sacred. There is no room for higher principles when we live so firmly in the concrete”.

Carlos Rojas is currently busy translating “Hard like Water”, which is also being translated for Editions Philippe Picquier by Noël Dutrait, professor emeritus,

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Yan Lianke, “La mort du soleil”, translated by Brigitte Guilbaud. Editions Philippe Picquier; February 2020, 385 pages, 22.50 euros.

(2) Yan Lianke, “Les jours, les mois, les années”, translated by Brigitte Guilbaud. Editions Philippe Picquier, February 2009, 128 pages.

(3) Yan Lianke, “The Four Books”, translated by Sylvie Gentil. Editions Philippe Picquier, September 2015, 515 pages.

(4) Yan Lianke, “The day the sun died”, translated by Carlos Rojas. Chatto &Windus London 2018, 340 pages.

(5) “The dream of the Red Chamber award”, awarded every two years by the Hong Kong Baptist University.

(6) Interviews: a/The Guardian 22/9/2018, Lesley McDowell.

b/ The Herald 1/9/2018, Jackie McGlone.

(7) The New Yorker 15/10/2018 “Yan Lianke’s forbidden satires of China” by Jiayang Fan; a first class interview.

(8) Yan Lianke, “Three Brothers, memories of my family,” translated by Carlos Rojas; Grove Press, 224 pages, March 2020.

(9) Yan Lianke, “Songeant à mon père”, translated by Brigitte Guilbaud, Editions P. Picquier ; 2010, 120 pages.