In February 2014, I posted a short analysis of the works of Xiao Hong, one of the most important novelists of 20th century Chinese literature, who died in Hong Kong in 1942, at the age of 31, after a ten years literary career. The anniversary of her death in 2012 provided the opportunity for strong media promotion: theatre production, opera and a film “Falling Flowers” by Huo Jianqi which did not meet with the success hoped for.

Two years later, the release of “The Golden Era” by leading filmmaker Ann Hui could have put Xiao Hong’s work back in the spotlight. Indeed, Ann Hui has made a number of quality films and recently in 2012, “A Simple Life”, who won many awards at the Venice Film Festival.

“The Golden Era” is a biopic, much too long, featuring famous actors including Tang Wei in the lead role. The staging is sometimes unnecessarily sophisticated; the lighting systematically seeks chiaroscuro, but who can surpass Rembrandt or Georges de la Tour?

The film says little about the novelist’s work and focuses on her love life, but it skillfully recreates the atmosphere of the time and evokes the relations between Xiao Hong and the great writer Lu Xun. He will support her and will have “Land of Life and Death” (1) published. After the death of Lu Xun in 1936, Xiao Hong wrote “A rememberance of Lu Xun”, a fascinating text about the daily life of this writer and his family and his relationship with Xiao Hong (2).

– A publishing work raise questions:

Les Editions de la Cerise, a publisher from Bordeaux, published in March 2019, an “adapted and illustrated” version of “Memories of Hulan Hé” (3), for which Shao Baoqing, a lecturer at the University of Bordeaux, thought he could write a preface. It is doubtful that such a “break up” of Xiao Hong’s work will have it appreciated by the French public, especially since the writer’s other novels are not even mentioned.

Simone Cross-Morea’s beautiful translation of the “Tales of the Hulan River” (4), does justice to this great book. The translator’s blog (www.xiaohong.fr ), which includes translations of Xiao Hong’s letters, is also worth a visit.

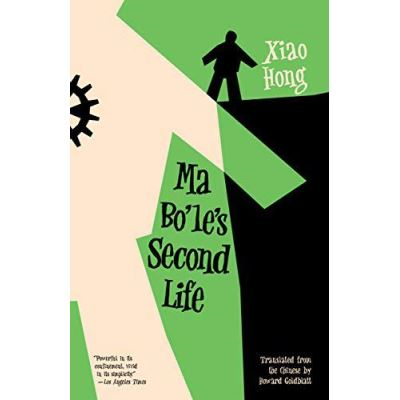

– Ma Bo’le’s second life” (5), a very special translation work:

This book is the last novel of the author who, before her death in Hong Kong, had published nine chapters. The book was translated into English by Howard Goldblatt, who completed it by adding eight more chapters and an introduction/conclusion, which takes place in 1984.

H. Goldblatt is a famous translator, he has translated about 60 Chinese novels and in the United States, the publishers consider that he is better known than the authors he translates and that this can be a guarantee to attract the reader.

His approach has upset some academics and translators. He sees his role as making novels acceptable to the American public. This can go a long way, for example in 2005, his abridged translation of Mo Yan’s novel “Big breasts, wide hips”, (825 pages in French (6) by Noël and Liliane Dutrait) does not exceed 240 pages in English. But he mentions as support Mo Yan’s approach, which states in substance “translation is your work and not mine, it is your responsibility”.

H. Goldblatt plays an essential role in making Chinese literature known in English-speaking countries and he is to a large extent responsible for the success of Xiao Hong. He translated most of her works and in 1976 wrote her biography. In 1980, he met Xiao Jun, the first husband, and in Harbin and Hulan, interviewed some of those who had known Xiao Hong. He even went so far as to translate a collection of short stories by Duanmu Honglian (7), her second husband. For Goldblatt, Xiao Hong is, along with Lao She, one of the essential writers of the first part of the 20th century.

When Goldblatt translated the book, he did not expect to find a publisher for an unfinished nine-chapter novel by a then little-known Chinese writer. So he decided to add eight chapters by making Ma Bo’le and his family reside in the cities where Xiao Hong herself had lived during the Japanese invasion.

He invented an introduction and a conclusion where, in 1984, David, Ma Bo’le’s son, had to give an opinion on a manuscript recovered by the Hong Kong Historical Society, the title and author of which are unknown but which they wished to publish, stating that Ma Bo’le “was a coward even before the war”. This made David strongly react, and he finally got the book qualified as “work of fiction”.

All this fiction does not help much. The chapters written by Goldblatt are of good quality; he does not try to imitate the style of the novelist, his descriptions are more fluid, more supported by historical or literary references. His fiction additions can be justified and altogether it is a pleasure to read.

The question remains: is this a novel by Xiao Hong and is the publication, as in China, of the first nine chapters not sufficient, especially since Xiao Hong describes Ma Bo’le’s personality and the characteristics of his family with great care?

– Ma Bo’le, an anti-hero:

The novel mocks the patriotism of the time; Xiao Hong dissociates writing and politics, doesn’t write, like so many others, anti-Japanese literature, which perhaps explains why her book was received without much excitement.

Women are at the centre of her work, most often herself; here the hero is a man, a character she wants to make an archetype of, like Lu Xun with Ah Q.

Realism, from which she is very far, was the official doctrine at the time; moreover, Ma Bo’le is a satire full of humour, a sort of picaresque novel. Ma Bo’le is the eldest son from a wealthy family in Qingdao. His father is a Christian and has given his descendants Western names, sometimes in an approximate way: Ma Bo’le’s daughter is called Jacob! Praise for the West, wearing Western clothes, studying English, praying and studying the Bible, these are the instructions for those around him.

Ma Bo’le has failed the university entrance exam. He lives with his wife and three children at his father’s house and has to ask his father for money. He claims he is willing to work and goes to Shanghai to set up a publishing house. His father’s money is quickly spent without any books being published.

The return home was difficult but with the Japanese aggression in June 1937, he returned to Shanghai convinced that Qingdao will be occupied. Living in poverty like a refugee, “his sadness had begun the day he was born…he gave the impression that life was little more than submitting to adversity” (p.97).

His wife joins him with the children and some money. They flee the Japanese advance in cities where Xiao Hong stayed: Nanjing, Hankou, Wuchang, Chongqing. A few vague ideas of activity but “soon he reverted to his old habit of sitting at home and brooding” (p. 181).

He observed troop movements and sometimes wanted to become a soldier, but this was not very attractive and, moreover, “with all the, time he spent watching these soldiers, he could almost be considered one of them” (p.179).

The family’s journey comes to an end, as does Xiao Hong’s life, in Hong Kong, which is occupied by the Japanese in December 1941. H. Goldblatt then details the fate of the various members and thus “completes” the novel.

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Xiao Hong, “Land of Life and Death”, translated into French by Catherine Vignal and Simone Cross-Morea, Panda , 1987.

(2) Xiao Hong, “A rememberance of Lu Xun”, published in 1940 and translated by Howard Goldblatt, released in the spring 1981 issue of the magazine “Renditions” (p.168 to 191).

http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/rct/pdf/e_outputs/b15/v15p169.pdf .

(3) “Memories of Hulan He” with illustrations by Hou Guoliang (already published in China); a version “translated” by Gregory Mordaga and “adapted” by Antoine Trouillard.

(4) Xiao Hong, “Tales of the Hulan River”, translated by Simone Cross-Morea, You Feng Publishing, bilingual Chinese French, 2011, 440 pages. The novel was also translated into English by Howard Goldblatt, “Tales of Hulan River”, Joint Publishing Hong Kong, 1988.

(5) Xiao Hong, “Ma Bo’le’s second life”, translated, “edited and completed” by Howard Goldblatt, Open Letter, 2018, 250 pages.

(6) Mo Yan, “Beaux Seins, Belles Fesses”, translated into French by Noël and Liliane Dutrait, Le Seuil 2004.

(7) Duanmu Hongliang, “Red Light”, translated by Howard Goldblatt; Panda 1988.