The end of the holiday period provides us with a major book from a Chinese novelist whom we had the pleasure to interview twice: Yan Lianke.

The end of the holiday period provides us with a major book from a Chinese novelist whom we had the pleasure to interview twice: Yan Lianke.

We remember for sure “Serve the People”, the “Dream of Ding Village”, “The Joy of living” published in 2009, and a beautiful text, “The Days, the months, the years”.

In “The Four Books”, he recalls the Great Leap Forward, the disastrous economic reforms imposed by Mao Zedong from 1958 to 1960, and the famine that followed, claiming the lives of 36 million people.

The themes of the book are in fact the madness and the suffering of men, the cynicism of the powerful, the cowardice of the intellectuals and a sense of absurdity that cannot be redeemed by religion or even human love.

The Great Leap Forward and the madness of men:

The novel opens with twenty pages in the style of Genesis and the Child, a teenager who heads the labor camp (zone 99) of intellectuals, “rightists” to be rehabilitated (the “novéducation”), reads to them the Ten Commandments, or rather the ten bannings of a totalitarian society.

He tells them that “the State is at the center of the universe … we will within two or three years revolutionize the world, we will catch up England and overtake the United States.”

To do this, we will need record crops and yields of cereals in a barren area south of the Yellow River and produce quantities of steel that will amaze the world.

Higher targets by the different camp leaders and the pressure from higher authorities, lead to unrealistic targets; they try to have them accepted with the promise of “good marks”, flowers, stars that could allow a release. Powerful weapons in the hands of the Child, who also controls the food. He is himself manipulated by the authorities who promise a trip to Beijing.

Deep plowing, sowing with very close intervals, wide scale irrigation while at the same time building small “blast furnace” where are melt all iron objects available and later sand with iron oxide.

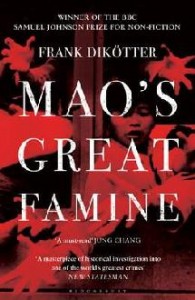

Yan Lianke as a novelist recalls this period that the work of Frank Dikötter (not translated into French) on “Mao’s Great Famine” (Bloomsbury 2010) describes as an historian. Yan Lianke focuses on the life of a camp; what he describes is confirmed by the historian, but Dikötter also reminds us of:

Yan Lianke as a novelist recalls this period that the work of Frank Dikötter (not translated into French) on “Mao’s Great Famine” (Bloomsbury 2010) describes as an historian. Yan Lianke focuses on the life of a camp; what he describes is confirmed by the historian, but Dikötter also reminds us of:

• The rivalry between China and the USSR for the leadership of the world revolution;

• the end of the Soviet aid;

• the need to fund in hard currency (therefore with grain exports) the huge imports of machinery and plants;

• aid to friends of China and revolutionary movements.

The book by Dikötter demonstrates the personal responsibility of Mao Zedong in this policy, the fight against his opponents, the inglorious role played by Zhou Enlai, both of them well informed of unmet targets and of the disorganization of the country as well as of the famine that accompanied the Great Leap Forward.

Within a few weeks will be released the French translation of the book, considered as a reference, by a Chinese journalist, Yang Jisheng, “Tombstone: an account of the Chinese Famine in the 1960s.”

The war against nature and the famine:

“The authorities said that if the country was in trouble, it was because of foreigners; they had grabbed China by the throat and caused the great famine”.

But the historian tells us that climate disasters and the termination of foreign aid are not adequate explanations.

But the historian tells us that climate disasters and the termination of foreign aid are not adequate explanations.

Mao Zedong launched a war against nature, he cut forests to manufacture bad iron, moved mountains for irrigation projects sometimes without lasting impact, eliminated birds guilty of eating seeds (but also insects and parasites)…

He lost the war and the disruption due to collectivization with forced march and a strong emphasis on cities and friends abroad in the distribution of cereals, led to one of the greatest famines in human history.

Others before Yan Lianke have described the famine and the camps, for example, Zhang Xianliang or Yang Xianhui, but they do not have the talent to create such emotion and… horror. Robberies, denunciations, half-buried corpses, landscapes of graves, cannibalism… we think of the major film by Wang Bing, “The Ditch”, presented a few months ago in France.

Intellectuals, writing and books:

Yan Lianke, is a peasant educated by the army, most of his books were censored or banned. He does not participate much in the official life of Chinese writers: “The Four Books” was published in Hong Kong in 2010.

His distrust vis-à-vis intellectuals was even the subject of one of his novels not yet translated. A character in his book, the Writer, wrote two of the four books: “The Memorandum,” a document denouncing other prisoners for the Child (who provided him with benefits and supplementary rations) and “The Old Bed “, the book he wants to finish on the life of the camp 99.

The Child has published a list of authorized books, the others must be handed. They will be exchanged against food and the Child will use them for heating!

“The Four Books”, has a style and a tone very different from his other works; it is read with admiration for the evocative power of the writer and the diversity of styles of the four books which mutually interpenetrate. Pages which will be remembered: the wheat that the Writer waters with his blood – but also scenes of great violence – the death of Music, the only woman among the main characters, and the only one capable of love and selfless love.

The novel is beautifully served by the translation by Sylvie Gentil, who has also translated “The joy of living”. In Beijing for 25 years, she also plays an important role in promoting the young generation.

The characters – the Scholar, the Writer, the Reverend, the Child, Music – are not schematic icons as their name might suggest, they have a real existence and even the Child, who will eventually crucify, finally obtains some of our sympathy.

The great writer is able to transfigure reality. Very cruel evocations sometimes take a universal value, especially as Yan Lianke confronts his characters with religions and myths.

Even if we say that Buddhism is privileged and if Confucian values are hardly present, Genesis, the four Gospels, and the Virgin Mary are central to many episodes: the Religious man eventually hates the Virgin the image of whom he has trampled. As for the Child, the struggle to eradicate religious books and pictures, paradoxically triggered his interest for these subjects.

The Myth of Sisyphus: Albert Camus and Yan Lianke

“New Myth of Sisyphus” is one of the four books, an unfinished philosophical essay on which the Scholar has worked extensively:

“Because he is able to accept the absurdity, pain and punishment, Sisyphus is for us a hero”.

Every day, he pushes his rock to the top of the mountain and then the rock rolls back down to its original position and in the morning he begins all over again:

“This cycle of back and forth … Sisyphus now considers it as his duty, his job. If he were to escape this time circle, his existence would be meaningless.”

In his book “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942), Albert Camus devotes a hundred pages to the absurd. The revolt is the only way to live a life in an absurd world and as mentioned in the last sentence of the book:

“The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy. “

Yan Lianke has a different approach: Sisyphus has enjoyed his punishment, the Gods then force him to push the stone downwards and it goes back alone to the top of the mountain! Punishment is no more” a power, a scourging, if the man can make the best of it, he will find beauty and meaning in his helplessness and submission.”

Sisyphus adapts to this stone which climbs the slope by itself and he will hide to the Gods his adaptation to circumstances. We dream about what could be an impossible dialogue between these two great writers …

Bertrand Mialaret.

“The Four Books” by Yan Lianke, translated by Sylvie Gentil. P.Picquier Editions. 410 pages, 20.80 euros.