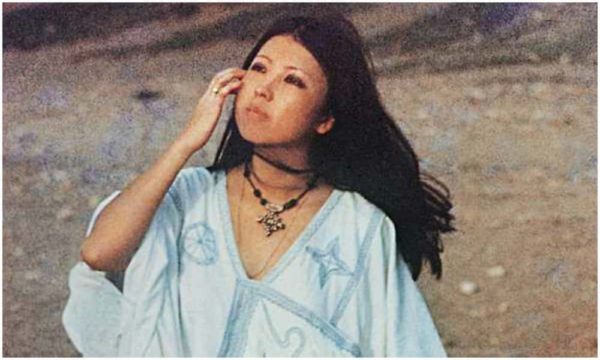

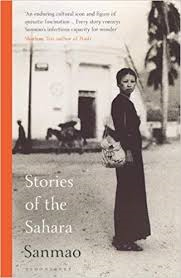

Nearly thirty years after her death, she remains a celebrity in China and Taiwan; a million followers on her Weibo account. Her best-known book “Stories of the Sahara” (1) has just been translated into English. A huge success in 1976 and ten million copies sold after a serial publication by the Taiwanese newspaper “United Daily News”.

Her memory attracts Chinese tourists, even to El Aaiun, the capital of the former Spanish Sahara, where she lived for three years with her husband José. In El Aaiun, there is a hotel, the San Mao Sahara, and in the Canary Islands, Sanmao tours are organized as well as a visit to the tomb of her husband José Maria Quero.

Similarly, in China, in Dinghai (Zhejiang), in the islands near Ningbo, a museum is dedicated to him where you can admire the camel skull that José gave her as a wedding gift. The Dinghai district even organized a Sanmao literary prize.

However, she is no longer the absolute reference for young Chinese women dazzled by her audacity, her love stories and especially her travels. More than 50 countries, which was exceptional in the 1980s, is no longer so amazing for the younger generation. Nevertheless, her very romantic existence makes her a unique personality.

– Studies and travels all over the world:

Chen Mao-Ping was born in 1943 in Chongqing to a Christian family from Zhejiang province; her father was a lawyer and she had one sister and two brothers. She took the pen name Sanmao in reference to the little character of Zhang Leping. In English, she was known as Echo or Echo Chan after the nymph of the Greek mythology.

In 1949, the family moved to Taiwan where Sanmao had difficulties with the very strict educational system. She reads a lot, Chinese literature but also Western literature. Following catastrophic results in mathematics, she stops school. Her father taught her literature and English and recruited a teacher, the painter Gu Fusheng, who encouraged her passion for literature.

A year of philosophy at the Taipei university and already at the age of nineteen, she began to publish. Then for four years, studies in Madrid, Germany and Chicago, with many travels and trips. She returned to Taiwan for a year where she taught but returned to Spain in 1972.

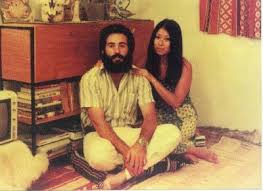

She meets again José Maria Quero, whom she had known when he was only sixteen years old. He is now a graduate and has done his military service. Sanmao wants to live in the Sahara, José finds a job with the phosphate mines of Boukraa, 50 kilometers north of the Spanish Sahara capital, El Aaiun, where they will rent a house; they will marry there in 1974.

– Sanmao and the Sahara:

“Stories of the Sahara” includes about twenty very different texts: the couple’s daily life in El Aaiun, their travels in the Sahara, their neighbours, how Sanmao became a teacher and a nurse in this feudal society, the troubles of 1975-1976, at the end of their stay.

El Aaiun, the capital, was founded in the 1930s after the discovery of groundwater. A small town for trade and Spanish colonial administration. They rent a house outside the centre, arrange it and furnish it with talent even if periodically goats jump from the roof into their accommodation.

Samao, independent and vigorously feminist, is also an interior woman. She feeds José very well sometimes with products shipped by her mother. “Married life is all about eating. The rest of the time is spent making money in order to eat. There really isn’t much more to it” (p.21).

But at the time, for her readers, a woman who married a foreigner, who lived in the desert far from her family and who had no children, was an exceptional transgression of social norms.

Few contacts with colonial life outside José’s colleagues. Almost no television and some newspapers with a lot of delay. She reads, writes and does not really complain about the monotony or the climate. Travelling is a great pleasure; “there is no other place in the world like the Sahara. This land demonstrates its majesty and tenderness only to those who love it” (p.332). They also sometimes go to the rocky and steep coast to fish and collect mussels and abalones.

Apart from a 2000 km honeymoon, these are short tours because José has very few holidays. They’re looking for fossils in the desert. José is caught in quicksand, a scary story (Night in the wasteland) where she is pursued by three Sahrawis.

Neighbours are an essential part of daily life. Sanmao has an ambiguous attitude; she constantly complains about their body odour because the Sahrawis hardly wash themselves. For the nomads, a bath every three or four years! But her door is always open, the neighbours and their children are at home all the time to borrow something, try on her clothes, chat… José is asked to repair the electricity in the neighbourhood… But when, in turn, they need a hand, the doors close.

She is very sensitive to the poverty of women, especially outside the city, to their disastrous state of health. There’s no way they are letting a male doctor examine them. She becomes a nurse, distributes medicines but José is against her acting as a midwife.

It is a feudal society. The marriage of her neighbour’s very young daughter, decided by her father and brother, the dowry to pay, the festivities, the wedding night, all this revolts her. Slavery remains present, she tells us in “The mute slave”, the story of a black slave and his family. Tribal leaders are the largest owners. The situation has improved, but slavery is still reported nowadays in the Sahrawi camps of Tindouf.

– A book which deserves to be famous:

A book that can be read easily even without knowledge of Chinese literature or Spanish Sahara. No scientific, historical or ethnological claims. The author of the preface, Sharlene Teo, a Singaporean novelist who has just published a good novel “Ponti” (2), quotes Sanmao “when I began to write, I decided to faithfully record the life of ordinary people whose voice go unheard”. Everyday life can be exceptional.

A very pleasant style, she almost speaks to us in the ear as a friend. Some descriptions, without emphasis, underline her love for the Sahara. She specifies her ideas, her dislikes, her revolts but without trying to convince the reader or to develop ideological or political presuppositions. She also has a lot of humour and the cultural ambiguities with José or the Sahrawis are often very pleasing. A great breath in this book, the desire for freedom.

– The 1975-1976 unrest and their departure:

The independence of Morocco, Algeria and Mauritania led these three countries to want to share the Spanish Sahara, becoming attractive with its large phosphate reserves. The first independence movements were created in the 1970s. Eleven people died in El Aayun; Mohammed El Basri, the leader, was murdered in prison.

In Lemseyed, a small oasis, Spanish soldiers are slaughtered in their sleep. Only one survivor, Sergeant Salva, who, too drunk, had not returned to the camp. A splendid text on this sergeant (p.246) where Sanmao recounts in a few pages, the events of the time.

The historical references are very limited, which can be embarrassing because she uses historical characters in a fictional way; for example in “Crying camels”, Bassiri reappears as the leader of the independentists and husband of Shahida, a nurse persecuted because she is Catholic. They were killed, in the book, by the Sahrawis in 1975.

Sanmao and José left the Sahara for the Canary Islands early 1975. Madrid was not an option because the relationship with her mother-in-law is rather complex. This has not created any difficulties between them and the book is a continuous love letter to José even if she highlights his defects, his weaknesses and their cultural differences.

José’s death in 1979 during a dive was a disaster. She returns to her parents’ house and then moves again to the Canaries.

In 1981, after six months in Latin America for the United Daily News newspaper, she successfully taught at the university in Taipei and published a lot: travel stories, fiction, translations, scripts… A Yim Ho film “Red Dust”, in 1990 with Maggy Cheung and Brigit Lin, was a great success.

Famous songs, including “L’olivier”, sung by Chyi Yu https://youtu.be/LZb8fJZFhlo and for which the translated text can be found (https://supchina.com/2019/04/07/friday-song-chyi-yu-the-olive-tree-san-mao/).

The last few years will be bleak because of cancer. She committed suicide at the Taipei hospital in January 1991. “In this life, I’d always felt I wasn’t part of the world around me, I often needed to go off the tracks of a normal life and do things without explanation” (p.171).

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Sanmao,’Stories of the Sahara’, translated by Mike Fu, Bloomsbury 2019, 390 pages.

(2) Sharlene Teo,’Ponti’, Picador 2018, 290 pages.