Originally published on Rue89, 09/06/2008 –

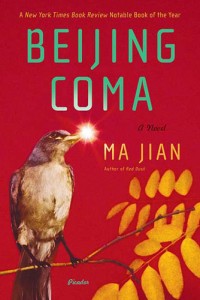

The release of the French translation of the book of Chinese writer Ma Jian, “Beijing Coma” is a real event, an important book on the tragedy of Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989.

The release of the French translation of the book of Chinese writer Ma Jian, “Beijing Coma” is a real event, an important book on the tragedy of Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989.

Three books in one: The hero, Dai Wei, wounded by a gunshot in the head inflicted by a plainclothes police officer when the army crushed the revolt of the “Beijing Spring”, will live ten years in a coma, which enables him only to hear people around him. In an attempt to escape, he clings to his memories and the suffering of his parents.

The author then mentions some of the tragic episodes in the history of Maoism choosing the sensational and without the evocative power of Yu Hua’s novel “Brothers” (Actes Sud, 2008), recently published, or the documents gathered by Song Yongyi on “The massacres of the Cultural Revolution” (Buchet Chastel, 2008).

The second theme concerns the daily life of the wounded. The police is around to arrest him if he recovers, neighbors spy on his mother, who has the greatest difficulties to survive and pay for medical treatment, when hospitals or traditional medicine accept to treat a victim of Tiananmen. Although long, this part of the novel allows a relatively complex construction which often manages to maintain our interest in a story of which we know, from the beginning, the tragic outcome …

His former classmates are helping his mother to care for him but gradually show the will to become rich in China and especially abroad. Also his body becomes a commodity: his urine would be miraculous and are sold as, later, one of his kidneys and he even becomes a sex object because this part of his anatomy still works!

His mother, a zealous Communist, was unable to join the Party because of her “rightist” husband and a son known to the police and, later on, security officer of the hunger strikers in Tiananmen Square. She will ultimately join the Falungong sect …

His mother, a zealous Communist, was unable to join the Party because of her “rightist” husband and a son known to the police and, later on, security officer of the hunger strikers in Tiananmen Square. She will ultimately join the Falungong sect …

Ma Jian collects, also with the mentioning of his banned book about Tibet, the almost complete list of “off limits” for the Chinese authorities! The importance given to the theme of coma come perhaps from the accident that brought, during the same period, Ma Jian’s brother in the same situation.

The third topic of the book concerns the sequence of events that led to the crackdown, by the army on June 4, 1989, of the student rebellion and to so many deaths.

Students onTiananmen square:

This topic is really new because these events had previously served as “background” to romance novels. Ma Jian tells us what his hero is seeing; this limits the approach of the “Beijing Spring” to its student component, excluding the support of Beijing population.

Similarly the root causes of the events are barely mentioned in particular the political situation after the events of 1987 and the significant role of a sharp rise in prices which made life much more difficult.

Ma Jian has a clinical approach of the events and their actors; he does not hide the unpleasant aspects of the power struggle between student groups, the attitude of some leaders trying to become a star. One has the impression of a roman a clef in which old scores are settled, especially as the debate between former exiled leaders on the responsibilities of the failure are still going on.

The cowardice of leaders is not hidden, the same goes with the sharing of a “war chest “… For many students, this is a big “happening” with music, drinks and flirting, as in the film “A Chinese youth” by Lou Ye …

All these pages, often boring, about debates on the strategy vis-à-vis the authorities, details of power struggles, do not hide the courage of some people, conscious of the historical character of the events they create and live and of risks they take and have their friends take. But, as underlined by Ma Jian, the movement lacked the sense of history by imagining that they could bring the authorities to retreat …

Ma Jian and Tiananmen:

Ma Jian is 55, he was born in Qingdao; the story of his family is as troubled as that of his hero. After a training as a painter and photographer, he worked as a photojournalist. A journey of several years in western China leads him to Tibet and to a collection of short stories “The Beggar of Shigatse” (Actes Sud 1988), a book that was banned as too negative vis-à-vis Tibetans, presented as primitive, violent and lacking ideal. This book, exposed as an example of “bourgeois liberalism” played a role in governmental discussions that led to a harsher approach in 1987.

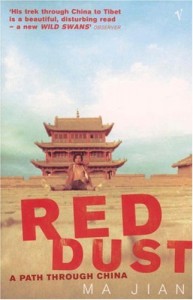

On his journey, Ma Jian writes an interesting book “Red Dust” (Editions de l’Aube, 2005) that must be read as a travelogue and has neither the ambition nor the talent of “The Soul Mountain,” the book of his friend, the Nobel Prize for Literature, Gao Xingjian, who shares some topics.

On his journey, Ma Jian writes an interesting book “Red Dust” (Editions de l’Aube, 2005) that must be read as a travelogue and has neither the ambition nor the talent of “The Soul Mountain,” the book of his friend, the Nobel Prize for Literature, Gao Xingjian, who shares some topics.

Leaving for Hong Kong in 1987, Ma Jian returned to Beijing to participate in the occupation of Tiananmen Square without special responsibilities; he is much older than the students. During the crackdown of the movement, he is in Qingdao to take care of his brother.

In Hong Kong, he will meet later Flora Drew, his translator and mother of their two children. They live in London where he feels exiled specially because he does not speak properly English; Flora translated his novels in English, the basis of the French version. He regularly returns to China where his mother lives and the girl he had from a first marriage. He is not published in China and is asked to avoid public statements during his visits.

A committed novel:Ma Jian is obsessed by the fact that these events are forgotten more and more in China and abroad. His book will be published in Chinese in Hong Kong and Taiwan and released on the twentieth anniversary of the crackdown, next year; an anniversary that will be carefully “prepared” by the authorities.

For him, Tiananmen marks a fundamental break with the loss of all ideals by the Chinese people; economic growth is not enough, we must revisit this tragedy in order to go forward on a sound footing. The government wants to write the story that suits him, the role of writers is to work for collective memory.

Paradoxically, he is in line with Mao: literature must “serve the people”. There he is separated from his friend Gao Xingjian who has always fought for the independence of the writer’s work and rejected all the “isms.”

Exile and Literature:

Some suggest that Ma Jian is far from today’s China, which is probably unfair because he seems a very careful observer. Others point out that progress in China on local conflicts are more the result of lawyers, journalists, heads of village honest and courageous.

The writers have only a marginal role unless they are involved in the country such as Yan Lianke or if their activities match hot topics, for example the book by Chen Guidi on “The Peasants in China today” (Bourin, May 2007), which was approved then banned but sold as pirate edition and had a significant impact.

Ma Jian’s relations with writers in China are difficult: he accuses them of not playing the role that the country should expect from them. At a meeting of English PEN’s last June 3, he explained that “there are only three possibilities for writers in China remain silent, say only what you are given permission to say (some heard “collaborate” at the meeting) or choose exile !

Bertrand Mialaret

► Beijing Coma by Ma Jian – translated from English by Constance de Saint-Mont – Flammarion, August 2008 – 630P., 23 €.