With the epidemic, sales of Camus’ “The Plague” strongly increased in Italy and France. A good omen for Chi Zijian’s novel “Neige et Corbeaux” (1) (White Snow, Black Crows) which has just been translated into French with talent by François Sastourné and published by Editions Philippe Picquier.

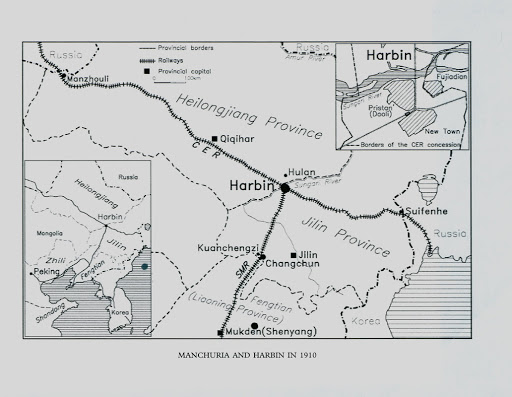

The novel was released in China in 2010, as an anniversary of the plague in Harbin and Manchuria that killed 60,000 people in 1910/1911. Harbin is now a city of 11 million inhabitants, north-east of Beijing, known worldwide for its ice sculpture competition.

Founded in 1898, Harbin grew rapidly with the Trans-Siberian Railway and had a population of 100,000 people, mostly Russians living along the Songhua River, a city that retains some very beautiful architectural features. On the other side of the river is the Chinese district of Fujiadian (now Daowai), which was quite miserable and has no comparable monuments.

The author has carried out an extensive documentation work that I could test on several subjects. She has the ability to bring to life this vision of the past and to create characters that illustrate this historical period.

Chi Zijian, a writer from the Far North :

She was born in 1969 in Mohe, one of the northernmost settlements in China where temperatures of minus 40 degrees Celsius are common. She has written wonderful short stories, three collections published In French by Bleu de Chine from 1997 to 2004, then “Toutes les nuits du monde” (3).

This was followed by a short novel about the Jewish community of Harbin, ” Goodnight Rose ” (2) and a magnificent evocation of the Evenki people, nomadic reindeer herders (” The last quarter of the moon”) (4). The translator of this book, Bruce Humes, writes some comments about the plague and translates into English pages of “White Snow, Black Crows”. (bruce-humes.com/archives/12934)

In “White Snow, Black Crows”, Chi Zijian wanted to revive Fujiadian before and during the plague epidemic by showing the impact of the disease on daily life and its limitations; “in other words, I wanted to put aside the bleached skeletons and describe life under the cloud of death” (p.360). Yet the number of deaths in Fujiadian has exceeded 5,000, or nearly three out of every ten people.

The characters are many and very diverse: an eunuch, Zhai Yisheng, a redeemed prostitute, a Russian singer, Sennikova, a restaurant, a distillery, grain storage areas. The town of Harbin is an important character.

Many aspects remind us of the Covid-19 epidemic that we are experiencing and the attitude of our fellow citizens who lack discipline; perhaps they think like in Harbin, that contagion is inevitable and that one must lead a normal life!

But the tone of the novel is not tragic, life goes on despite the deaths and quarantines. The book comes back after several chapters on many characters that we thought forgotten. This is why we can regret that the publisher did not give us the necessary gift of a list of characters and their relationships.

Crows, a protective animal:

We meet these birds often: children play with them, some inhabitants feed them regularly, they nest in the tops of trees. In Harbin, they sadly accompany the funeral whereas before the confinements, it was a festive occasion.

In Europe, they are certainly associated with winter, but also with poverty and misfortune. In Manchuria, they are not at the origin of the plague epidemic that comes from marmots and their hunters. The Manchu people revere them just like the swan and the dog. They do not eat dogs and do not use their skins.

Nurhaci, founder of the Qing Dynasty, was saved by a group of crows who hid his body and allowed him to escape from his enemies. In thanksgiving, in the centre of the courtyard of the Shenyang palace, stands a seven-metre wooden pole with a receptacle to feed the crows and offer a sacrifice to Heaven.

A dramatic epidemic:

In Wuhan, the coronavirus outbreak was correctly detected but some city CP officials forced the doctors to keep quiet. The situation in Manchuria was different but poorly assessed: the first step was to fight against a bubonic plague by trying to eliminate the vectors, the rats.

The epidemic spread rapidly, with the Russians and Japanese controlling the railways putting pressure on the Chinese government so as the consuls of various foreign countries. It was then that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs asked Wu Liande, recently invited as vice-director of the Tianjin Medical School, to go to Harbin to investigate the disease.

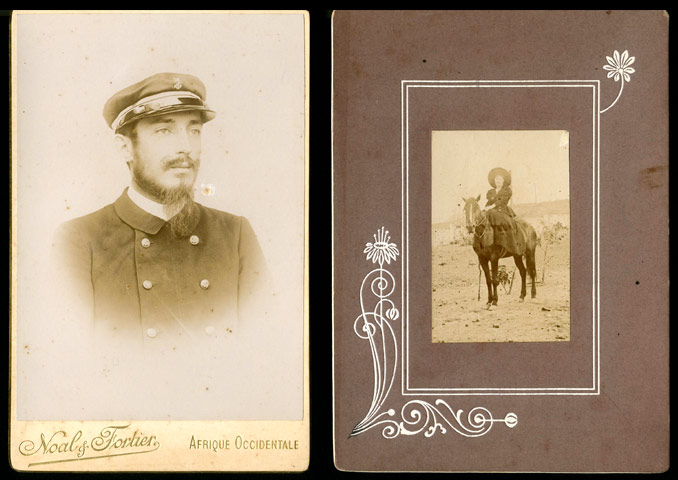

Chi Zijian chooses “not to model a heroic character in (her) novel, although Wu Liande is the hero who has restored the situation”, (p.359). Wu Liande (1879-1960) was born in Penang, Malaysia, to a new immigrant father and a second-generation immigrant mother. He was educated in Penang and then in Cambridge. A brilliant academic and then clinical career at St Mary’s Hospital in London.

In Harbin, he hardly speaks Chinese, but he has an assistant Li Jiarui. He begins by dissecting a corpse to discover that it is in fact a pneumonic plague that is transmitted directly from man to man. This discovery is not accepted by Dr. Hoffkine, the director of the Russian hospital and by a Frenchman, Dr. Gérald Mesny, sent as a reinforcement by the government and who, unhappy to be under the authority of a young Chinese, will try unsuccessfully to get rid of him.

Wu Liande will very quickly implement the techniques to control an epidemic that we hear about every day: no contacts, masks, quarantine, travel control…. The town of Harbin is cut off from the world by the army. The corpses that could not be buried because of the frost are incinerated, a decision taken “at the highest level”. Railway carriages are used as a field hospital. Even the Catholic Church in Harbin and its French priests had to submit and evacuate the sick they were hiding.

A colonial conflict:

Doctor Gerald Mesny, who, despite the support of the French legation, failed to oust Wu Liande, continued his medical job, but without the protection of a mask, he will die of pneumonic plague.

An obituary appeared in a French newspaper in Brest on 4/3/1911 entitled “A dictator of hygiene in China”. We have forgotten the tone of these colonial chronicles; this one is hallucinating by its style when it speaks of China, by its contempt, by its oversights on the misdiagnosis of a doctor who is praised for his contribution to the greatness of France.

A monument in his memory was inaugurated in Brest in 1921, then it was melted down. The small bust is kept in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

As for Wu Liande, he was decorated, chaired the International Conference on the Plague in Shenyang, published in The Lancet and remained in China until the Japanese occupation. In 1937, he returned to Malaysia, to Ipoh, where he worked as a general practitioner and treated the poor free of charge. He opened the Tun Razak Library in Ipoh and retired in Penang at the age of 80. An association supports his memory there and his daughter wrote his biography (5).

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Chi Zijian, “Neige et Corbeaux”, translated into French by François Sastourné, P. Picquier, 2020, 360 pages, 21.50 euros.

(2) Chi Zijian, “Bonsoir la Rose”, translated by Stéphane Lévêque and Yvonne André; P. Picquier, May 2015, 185 pages, 20 euros. (In English, “Good Night Rose”, translated by Poppy Toland, Penguin China Books, October 2018, 180 pages)

(3) Chi Zijian, “Toutes les nuits du monde”, translated by Yvonne André and Stéphane Lévêque; P. Picquier, 2013.

(4) Chi Zijian, “Le Dernier Quartier de Lune”, translated by Yvonne André and Stéphane Lévêque ; P. Picquier, September 2015, 360 pages, 22 euros. (In English, « The last quarter of the moon », translated by Bruce Humes, Harvill Secker 2013, 320 pages).

(5) Wu Yu-lin, “Memories of Dr Wu Lien Teh: Plague Fighter”, reprinted by Areca Books, 2016.