c

When a book is recommended by readers of Rue 89, the French translator, Emmanuelle Péchenart, Actes Sud publishers, Isabelle Rabut and Angel Pino, the American translator, Michael Berry and in addition related to a successful film “Seediq Bale “, you start to be anxious fearing to be disappointed. Wrong,” The Survivors “is a great book …

When a book is recommended by readers of Rue 89, the French translator, Emmanuelle Péchenart, Actes Sud publishers, Isabelle Rabut and Angel Pino, the American translator, Michael Berry and in addition related to a successful film “Seediq Bale “, you start to be anxious fearing to be disappointed. Wrong,” The Survivors “is a great book …

1 – Some milestones:

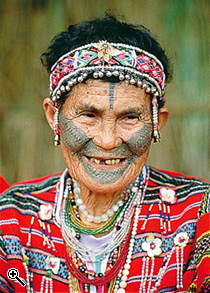

Aborigines of Taiwan, the first occupants of the island, represent less than 500,000, or 2% of the population. 14 groups can be listed of which the Sedeq who have just been “administratively” separated from the Atayal (a unit of 80,000 people living in the Northern part of the island) of which they were previously part. These are the tribes that are at the heart of the novel by Wuhe (1) and who suffered during the history of Taiwan.

The Dutch, who occupied the south of the island for forty years, are driven out in 1662 when Koxinga, loyal to the Ming and escaping the Manchus, fled to Taiwan. In 1683, the island came under the administration of Fujian Province and Chinese emigration accelerated (3,000,000 in 1860), forcing the natives to take refuge in the mountainous areas.

After the Chinese defeat, the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, handed over the island to Japan until 1945. An assimilation policy is implemented, the Japanese language is compulsory, traditional tattoos and dental ablations are prohibited. In 1926, the Atayals hand out 1300 guns, “the weapon being the greatest possesion of a hunter” (p.90) but the skulls, “sacrificial objects” are kept.

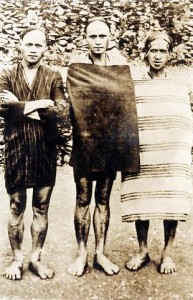

In October 1930, an incident between the son of Mona Rudao, chief of a Sedeq tribe and a Japanese policeman, led to the murder, by ‘mowing’ their heads, of 130 Japanese who were attending a sporting event in Musha. The massive replica of the Japanese with modern weapons, led to mass suicide of the Sedeq. In April 1931, the aborigines of another Sedeq tribe, the Tuuda, at the instigation of the Japanese, “mowed” a hundred bodies!

The survivors were deported to the village of “the island between two waters.” And that’s where Wuhe will stay in 1997 and 1998 to investigate the “Musha events”.

Wuhe is the pen name (“the crane which dance”) of Chen Guosheng, born in 1951 and graduated from the Chenggong University of Tainan. He published short stories from 1974 to 1979 and for thirteen years lead a secluded life and claimed to try to understand Taiwan and its culture. In 1999, the publication of “The Survivors”, and its many literary awards, is considered a major event. The same goes for the film “Seediq Bale” by director Wei Tesheng, the most expensive film in the history of Taiwanese cinema, presented a few months ago in Venice.

An important writer but a single work is translated as we can see from the book on “Taiwanese literature. State of research and reception abroad “(2), a general survey edited by Angel Pino and Isabelle Rabut.

However, the novel has been analyzed in depth by David Der-Wei Wang (3) and by Michael Berry (4) who is also currently translating the book into English.

3 – Steam of consciousness and various styles:

This 270-page novel has only one paragraph and almost no punctuation. This presentation of stream of consciousness can be confusing at first but we should not be impressed as all transitions are cleverly handled and the translation, very fluid, is read with pleasure.The author forces us to be close to him, to his intellectual and sensitive journey.

No real story, a series of sketches, interviews, anecdotes, reports, ethnographic notations. A set of meetings: Baku and Danafu, the Sedeq graduates, the pastor, a nun, the Vagabond, the brother of the Girl and many others; an old Tuuda, head hunter, Shabo who worked for the Japanese army.

No real story, a series of sketches, interviews, anecdotes, reports, ethnographic notations. A set of meetings: Baku and Danafu, the Sedeq graduates, the pastor, a nun, the Vagabond, the brother of the Girl and many others; an old Tuuda, head hunter, Shabo who worked for the Japanese army.

The author dialogues with himself, trying to understand what really happened, what is hidden, what has been forgotten; a great effort of empathy towards the survivors.

The hero, as Wuhe, is somewhat traumatized and investigating the “events of Musha” is also a way to appreciate what is happening, what has happened to him.

One thinks of certain fiction techniques in “The Soul Mountain” by Gao Xingjian the Nobel Prize, but also of their common search for primitive roots, Miao on one side, and Atayal Sedeq on the other.

David Der-Wei Wang puts in perspective Wuhe and the great writer Shen Congwen stressing that both try to link Aboriginal culture and Han culture, but he clarifies immediately that “Shen Congwen draws the power of his writing from an” imaginary nostalgia “…by contrast, Wuhe comes across as a practitioner of literary melancholia “(p.36). But it is true that you can bring together the executions in ” The Little Hunan Soldier “(5) and the” mowing ” of heads.

The Girl is an important figure; back to the village after a failed marriage to an Atayal and the abandonment of her children. After a period in a brothel in town, the village protects her from the pimp trying to take her back, but she will be “serving” men of the village.

She will walk upsteam along the river with the author in search of ancestral territories; it will be the last episode of this quest in the novel.

4 – The ‘mowing’ of heads, is it an act of resistance?

For the Kuomintang and for some Han comments, the “Musha events” are an act of resistance against Japanese occupation. Mona Rudao should be honored as a hero. Coins are minted in 2001 bearing his image, after a stele and a statue comes a memorial museum in 2001 in Chuanzhongdao, and even in 2005 a glorification … by a hard rock band that will tour the U.S. !

The reality is less simple.The old, tatoed Tuuda “says that what one feels in mowing the heads, is a pleasure that has no equivalent, indescribable …” (p.165). However with this practice of “mowing”, individuals are deprived forever of their autonomy, human existence takes place forever in the prospect of being killed or killing others, in the long flow of history, life goes on in terror, in the imminent prospect of being massacred which leads to massacre others “(p.238)

The reality is less simple.The old, tatoed Tuuda “says that what one feels in mowing the heads, is a pleasure that has no equivalent, indescribable …” (p.165). However with this practice of “mowing”, individuals are deprived forever of their autonomy, human existence takes place forever in the prospect of being killed or killing others, in the long flow of history, life goes on in terror, in the imminent prospect of being massacred which leads to massacre others “(p.238)

Are the “Musha events”, a mere traditional “mowing” but on a large scale, this is possible because there was no resistance against Japan for over ten years, but this finding is not politically correct !

The “events”, are they also for the Sedeq an act of “dignity”, dignity in the “mowing” and in the suicides that followed.

What is certain is that the lives of the”Survivors” was a life of suffering and shame; self-destruction by alcoholism which is a way to reject assimilation. It is the same for women prostitution in the city;

It is clear that the same causes produce the same effects that are underlined by the recent interest in aboriginal civilizations whether in Australia with the struggles for land and speculation about the “primitive” art or in New Zealand, as was shown in the recent exhibition “Maori” at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris.

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Wuhe, ” Les Survivants”, novel translated into French by Esther Lin-Rosolato and Emmanuelle Péchenard. Preface and notes by Angel Pino and Isabelle Rabut. Actes Sud, 2011, 295 pages, 23 euros.

(2) “The Taiwanese literature. State of research and reception abroad “, texts edited by Angel Pino and Isabelle Rabut. You Feng Editions 2011, 680 pages, 30 euros.

(3) “A History of Pain: Trauma in Modern Chinese literature and film,” Michael Berry, Columbia University Press, New York, 2008.

(3) “A History of Pain: Trauma in Modern Chinese literature and film,” Michael Berry, Columbia University Press, New York, 2008.

(4) “The Monster That Is History”, David Der-Wei Wang. University of California, 2004.

(5) ” The Little Hunan Soldier”, Shen Congwen, translated into French by Isabelle Rabut. Albin Michel, 1992.