Jean François Billeter is a well-known Swiss sinologist and professor emeritus at the University of Geneva. Some of his books are references such as “The Chinese Art of Writing” (1), which has been translated into English, studies on Zhuangzi (2), an essay on the contemporary history of China, “China three times silenced” (3). Other books deal with philosophy, politics, translation; the sinologist even becomes a polemist in his excellent “Contre François Jullien” (4), the famous French sinologist and philosopher.

This is why two recent books have left their mark on people’s minds, “Une rencontre à Pékin” (5) and “Une autre Aurélia” (6), a tribute to his wife Wen, who died in 2012. He met Wen and her sister in Beijing at the home of Mrs Li who, having retained her Swiss nationality, was allowed to receive foreigners.

After studying in Basel and then Geneva, J.F. Billeter decided, without enthusiasm, in 1962, to study Chinese in Paris at Langues O. He continued his studies in Beijing in 1963, then in September 1964 at the Faculty of Arts of the Beijing University on a Swiss scholarship (diplomatic relations had existed between Switzerland and China since 1950). Intensive studies but he is completely cut off from Chinese life.

Wen is a doctor and has been working for a year in the small hospital of a factory; she was born in Beijing, the sixth in a family of seven children. They manage to meet again but the police intervene and tell Wen that they must either stop seeing each other or get married. While they hardly know each other, they decide to overcome all obstacles.

– The private sphere is State business:

At the time, in China, no one could get married without the authorization of their work unit, a “letter of introduction”; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is delaying the decision but the Swiss ambassador introduces the two lovers to Marshal Chen Yi, Minister of Foreign Affairs. They continue to meet but are followed by plainclothes police officers and the police explains to Wen that her fiancé is a foreign agent.

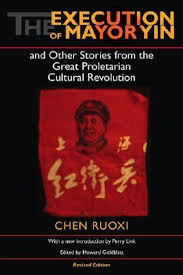

China is on the eve of the Cultural Revolution, a period brilliantly described by the Taiwanese author Chen Ruoxi (7) whom J.F. Billeter, rightly, admires very much. “The regime maintained with all the means of its propaganda a real paranoia: the class struggle was merciless, the enemy was everywhere, the one from the outside too…” (p.52).

They are finally allowed to marry, but Wen has to leave the hospital of her telecommunications company. The parents are informed of the marriage and at first are not happy. Wen gets a one-year leave and they can go to Switzerland where she obtains the dual nationality that China then recognized.

A first return to Beijing in 1975 to advance his thesis on Li Zhi, but the universities are closed; they will settle in Japan in Kyoto for two years. The thesis progresses and a little boy is born. Visas for China are not granted. Wen’s family has suffered a lot, her father is forced to sweep the streets wearing a yellow star, then he suffers from hemiplegia.

Many years later, Wen’s second brother gave them a note book about the family’s history, about the military career of her father, a follower of Chiang Kai-shek, but especially close to Zhang Xueliang, the “young marshal” who arrested Chiang and forced him to accept a united front against Japan. Wen’s family, very prosperous for a long time, lived with great difficulty in the 1960s and the situation will worsen with the persecution of the Red Guards, which the book describe in detail (pp. 130-134).

New misfortunes, her younger sister died in 1976 in the Tangshan earthquake and its 250,000 victims. Her mother died in 1977 and her father two years later. In general we don’t talk much about recent history, it remains unspoken, we don’t learn from it and events over time are forgotten, erasing the past which is what the regime wants.

– Absence and presence:

Wen died in November 2012; for a few months J.F. Billeter filled notebooks and wondered if the experience of grief could be shared and if he could suggest to others that they learn something from it. A small book “Une autre Aurélia” completes the first book.

No details about Wen, no anecdotes but thoughts about absence and presence. “Remembrance is the beginning of a presence that is formed in us. Nothing interrupts this development, this interruption causes astonishment. I have found a way to avoid it: accept the emerging memory as a form of presence without adding the idea of absence” (p. 18).

You have to refuse the word mourning, “the sinister vocabulary of death, of loss…now makes me horror…It prescribes to me the emotional value I’m supposed to give to my emotion. It deprives me of the freedom to interpret it as I see it or to let it be transformed” (p. 26)

As the author says, it is a book on emotion, “we don’t choose our emotions but we choose how to interpret them”. J.F. Billeter points out that he “is beginning to imagine our adventure from her point of view. That’s something that Proust did not mention”.

“Aurelia”, is it an adapted title? Wen has nothing to do with the actress Jenny Colon, Aurelia’s heroine, and J.F. Billeter is far from Gérard de Nerval and his fits of madness. Certainly Doctor Blanche, the doctor who treated G. de Nerval, had understood the therapeutic value that writing can have and had pushed him to write “Aurelia”. “Another Aurelia”, this great book, is perhaps also a form of therapy…

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Jean François Billeter, “L’art chinois de l’écriture”, Skira, Geneva, 1989, 320 pages.

(2) Jean François Billeter, “Etudes sur le Tchouang-tseu”, Editions Allia, 2006, 290 pages.

(3) Jean François Billeter, “China three times silenced”, Editions Allia, 2000, 148 pages.

(4) Jean François Billeter, “Contre François Jullien”, Editions Allia, 2006, 122 pages.

(5) Jean François Billeter, “Une rencontre à Pékin”, Editions Allia, 2017, 150 pages.

(6) Jean François Billeter, “Une autre Aurélia”, Editions Allia, 2017, 92 pages.

(7) Chen Jo-Hsi, “Le Préfet Yin”, introduction and translation by Simon Leys. Denoel Publishing 1980, 270 pages.

English translation by Nancy Ing and Howard Goldblatt, Indiana University Press, 1979, 220 pages.