Three books, two (1-3) by the novelist and poet Qiu Xiaolong and the third (4) by the sinologist Robert van Gulik, bring inspector Chen Cao, the favourite character of Qiu Xiaolong readers, into the Tang Empire (618-907) while investigating in Shanghai a murder committed by Min, a famous “private table hostess”.

Min recovered the family house after the Cultural Revolution; beautiful and cultured, an icon of the internet, she invites different personalities to private dinners where they discover subjects of common interest during a gastronomic dinner prepared by Min and by Qing, her assistant.

The murder of Qing (1) is taken care of, to Chen Cao’s surprise, by the Internal Security and not by the Shanghai Police. Min disappears with the procedure of “shuanggui”, generally used for Party cadres and mentioned by the author in one of his previous novels (2); it is necessary to avoid the media in this investigation which is not in the interest of the Party!

Inspector Chen, has been appointed Director of the Office for the Reform of the Judicial System, “a position without real power”. He is asked by former partners to take an interest in Qing’s murder. He is surprised by this murder which makes him think of the investigation by Judge Ti (630-700) that he is reading and that Qiu Xiaolong has mentioned in a recently published novel (3).

Judge Ti is trying to understand how a famous poetess, Yu Xuanji (844-871), during the Tang Dynasty, was able to kill her servant and bury her without assistance.

This historical episode is well known and had already been described in 1968 by the diplomat and sinologist, Robert van Gulik, in the last of his novels, “Assassins and Poets” (4). Judge Ti succeeds in obtaining from Yu Xuanji a confession that elucidates the murder without threatening the Empress and her son Li. Yu Xuanji’s life before her execution is also mentioned by van Gulik in his classic book “Sex Life in Ancient China” (5).

Chen Cao feels himself very close to Judge Ti, who, like him, is going through a depressing professional period of a life devoted to high public office and politics. As for Chen Cao, poetry for Ti is an important part of his life, as is the will to leave behind him a somewhat legendary image of a civil servant with integrity.

– Judicial reform and the law:

Chen Cao is asked to publish a statement about the daring photos of a judge, Jiao, which create a huge scandal on the internet. This judge was a Party commissioner in the army; like many of his colleagues, he has no legal training, but he is devoted to orders; “the law, like everything else, is subject to the goodwill of the Party” (1p.58).

Chen will point out that evidence obtained illegally does not constitute admissible evidence in other countries. Jin, his secretary, who is pretty, cultured, independent, and of course susceptible to the inspector’s charm, will edit the press release that all media will use to support Jiao.

Chen Cao must be involved in the judicial reform and makes some contacts. Is the Party above the laws? Should judges serve the Party or the law? The official answer is that “our judges serve the law in the name of the Party” (1p.173).

An answer that cannot satisfy Chen Cao, “For years he had believed that, by working conscientiously within the system, he would be able to change things, but he now has to recognize that his hopes had been only wishful thinking. Gradually he became aware of his own powerlessness” (1 p.108).

Corruption is felt everywhere, but its modalities are changing: Min’s private dinners allowed the real estate developer, Shuang Guanhua, to carry out a very profitable project and Min to recover half of the profit to, she says, pay the Party executive who made the operation possible.

Another guest, the antique dealer Huang, underlines the very high prices of antiques and indicates that “some Party cadres refuse bribes in cash but accept antiques. If one day they are under scrutiny, they can always pretend that these are cheap counterfeits. » (1 p.76)

– Poetic works and television series:

Trying to trace Yu Xuangji’s poems, in fact allows Judge Ti to make progress with his investigation. For Chen Cao, his friends, thrilled by his references to Judge Ti’s investigation, would like him to pilot TV series on the famous judge. Other times, other priorities!

Yu Xuangji is a courtesan who, very young, was sold to a brothel. Her lovers, especially the poet Wan Tingyun, to whom she dedicated her most beautiful poems, made her famous. Van Gulik and Qiu Xiaolong liked “A Winter Evening”:

– Inprisonment and “shuanggi”:

Judge Ti wants to meet the poetess in prison; he is amazed by her conditions of confinement; he gets her to wash, dress properly, and get a good dinner. She had been whipped in public because she stubbornly repeated an incredible version of the murder.

Judge Ti’s humanity allows him to convince Yu Xuangji to deliver an acceptable version while protecting the high-ranking character who was visiting her and who left her, leaving a yellow dress embroidered with a dragon and without trying to protect her.

Min is locked up in a hotel, she disappears; she is fed and not tortured, but some high-ranking figures fear that she will speak and it is fate that will lead the policewoman, Wanxia, to eat a dish prepared for Min and die poisoned.

The dangers accepted by Chen Cao’s secretary Jin, will make it possible to uncover the murderer of the assistant of Min and of the antique dealer Huang; Min should then be released and Chen Cao is invited, to his great surprise, by the Secretary of the Shanghai Police Party to holidays in the Yellow Mountains, one of the most beautiful sites, celebrated by generations of painters and poets.

They probably wanted to move him away to allow Internal Security to develop a correct version of the Min case or perhaps to get rid of Chen Cao for good. The future is unpredictable, a few days later, he is invited in Beijing to a seminar of the Party Academy, which has to prepare the opening of a central office of the reform of the judicial system in Beijing that Chen could lead.

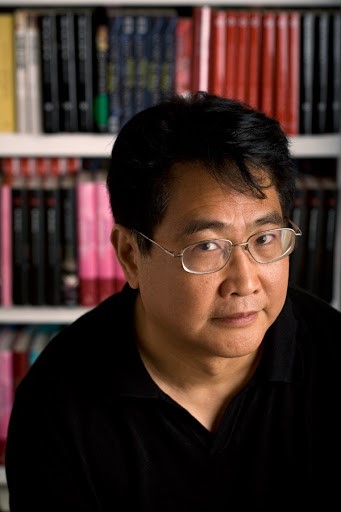

Qiu Xiaolong and van Gulik, around Judge Ti :

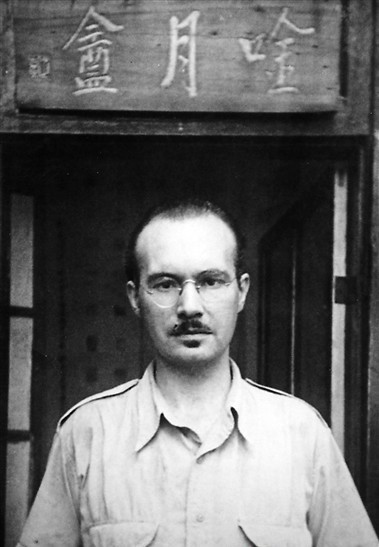

Robert van Gulik (1910-1967), was born in the Netherlands and spent part of his childhood in the Dutch Indies; he studied at the University of Leiden and went on to join, as an interpreter, the diplomatic corps. A career that will lead to the post of ambassador in Tokyo but also to a life as an orientalist scholar. A long stay in Chongqing, during the war, where he began the long series of Judge Ti’s investigations (16 novels in English).

One must mention van Gulik’s qualities, the complexity of his plots, his use of tradition (especially the role of the foxes) and sometimes his recallings of the period of the Tang. In “Assassins and Poets”, an interesting character, the academician Chao, as complex as he is unpleasant, who commits suicide because he does not want to owe anything to the poetess who adores him, for him, “a vulgar whore”.

A style very different from that of Qiu Xiaolong. A writing a bit rigid, more traditional, an impression reinforced by the rather classical engravings drawn by the author. Judge Ti is more of a character than a person, he cannot move us or please us like Inspector Chen. Ti is faithful to the dynasty, he accepts the system with its flaws and is less disillusioned than Chen. Poetry and gastronomy are part of the pleasures of life, but it is not like Chen Cao, an essential part

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Qiu Xiaolong, “Un dîner chez Min“, translated into French by Adélaïde Pralon; Liana Levi 2021, 250 pages. (Original English title “Inspector Chen and Judge Dee”).

(2) Qiu Xiaolong, “Cyber China”, Liana Levi, 2012.

(3) Qiu Xiaolong, “Une enquète du vénérable Juge Ti”, translated by Adélaïde Pralon, Liana Levi, 140 pages. 2020. (Original English title “The shadow of the empire”).

(4) Robert van Gulik, ” Assassins et poètes “, translated by Anne Krief. 10-18, 1985, 280 pages.

(5) Robert van Gulik, “La vie sexuelle dans la Chine ancienne”, translated from the English by Louis Evrard, Gallimard 1971.