Two films by Wang Bing are just released: “Fengming, chronicle of a Chinese woman,” an amazing documentary film, three hours long, where a long time Communist recounts her life and the death of her husband in a camp, in a casual and controlled way, but where one can feel love and humanity. “The Ditch” is a film that deals with a camp for “reeducation through labor” and the famine of 1960. Both films are directly inspired by a collection of short stories by Yang Xianhui.

Two films by Wang Bing are just released: “Fengming, chronicle of a Chinese woman,” an amazing documentary film, three hours long, where a long time Communist recounts her life and the death of her husband in a camp, in a casual and controlled way, but where one can feel love and humanity. “The Ditch” is a film that deals with a camp for “reeducation through labor” and the famine of 1960. Both films are directly inspired by a collection of short stories by Yang Xianhui.

1 – Stories by survivors called “fiction”:

Xianhui Yang was born in 1946 in Gansu, he finished high school in Lanzhou in 1965 and was sent “to the country side” in a farm in the Gobi Desert. There he meets former “rightists” and he hears for the first time the name of the Jiabiangou camp. He stays sixteen years in this farm until 1981, as a farmer then as a commercial clerk in the farm shop, later as an accountant and a teacher.

He began writing, publishing some short stories and moves toTianjin, where he still lives today and becomes a “professional writer”. In 1997, he visited Jiabiangou, there remains almost nothing. He is denied access to provincial archives, but he learns that it is only in 1987, following protests from farmers that the bones were completely buried!

For five years, he will trace a hundred survivors and manages to have them talk. In 2000, he published in the journal “Literature of Shanghai” the short story “A woman from Shanghai,” which creates a shock in public opinion, then a further eleven stories. In 2003, a book “Farewell to Jiabiangou” is published. The short stories have received numerous awards and much attention particularly in Gansu.

This is officially fiction while these texts are “reportage literature” often close to interviews.

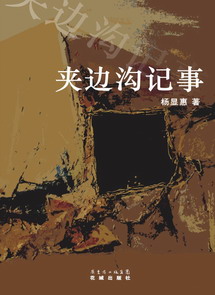

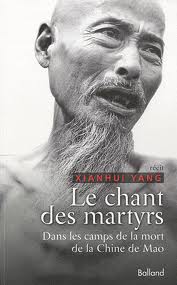

The translator, Wen Huang, a journalist living in Chicago, was sponsored by the PEN Center and worked with the author to “adapt” nineteen short stories to be published in English in 2009 (1). This text was then translated into French and published by Balland in June 2010 (2). It is interesting to compare the three covers of the same book: the Chinese with the input of an underground dormitory, the American with a beautiful lady supposed to be a selling point, the French, not very adapted …

2 – Literature and stories about the camps:

The literature on labor camps is important and has to tell the world a phenomenon of considerable magnitude that the younger generation in China does not know or is not willing to know.

The literature on labor camps is important and has to tell the world a phenomenon of considerable magnitude that the younger generation in China does not know or is not willing to know.

The literary quality is not always in line. Works by a major writer like Zhang Xianliang (3), testimonies like that of Jean Pasqualini, son of a Corsican father and a Chinese mother, who spent seven years in a camp and was released in 1964 following the estabishment of diplomatic relations between China and France (4).

It is important to distinguish the “Lao Jiao” education through labor, for people who have made mistakes rather than “crimes” (which was the case with the majority of “rightists”) and “Lao Gai “, reform through labor. In theory, the “Lao Jiao” lasts three years and civil rights are preserved during the stay at the camp.

These camps should not be confused with farm / camps organized in Xinjiang by the People’s Liberation Army (Corps of Production and Construction in Xinjiang). This huge organization, known as the Bingtuan, managed directly by Beijing, has been following the traditional system of “tuntian” that installs in the border areas military units that need to establish themselves, grow and develop their self subsistence.

Regarding the ” Lao Gai” one can read with interest the books by Harry Wu, who spent 19 years in various camps (5) and who, today the United States, leads the “Laogai Research Foundation” and has created the Laogai Museum in Washington (http://laogaimuseum.org).

3 – The “Hundred Flowers”, rightists and the “Great Leap Forward”:

In 1957, after a year of social unrest and the VIIIth Congress of the Communist Party, which shows a divided leadership, the objective was to improve the work style by mutual criticism. The slogan “let a hundred flowers bloom” and the temporary liberalization of the press, led in May-June 1957 to an explosion of criticism.

The government felt threatened and reacted quickly and vigorously. The “anti-rightist” campaign sent about 500,000 rightists in camps for reeducation through labor by simple administrative decision and without conviction by a court.

The government felt threatened and reacted quickly and vigorously. The “anti-rightist” campaign sent about 500,000 rightists in camps for reeducation through labor by simple administrative decision and without conviction by a court.

The legal profession, academia, civil servants were particularly targeted as well as a number of writers including Ding Ling.

In 1958, the “Great Leap Forward”, a political mobilization, totally unrelated to the economic reality, will end in an economic collapse worsened by the end of the Soviet aid and natural disasters.

The famine of 1960-1962 resulted in around 30 million deaths (6) and a deficit of births at least equivalent. It is against this background that life and death develops in the Jiabiangou camp in the north of Gansu, on the edge of the Gobi Desert, which had up to three thousand prisoners. Late in 1960, when the camp was closed at the request of the central authorities, there were only 500 survivors (who were sent home) and a doctor who took care of the archives to report diseases while prisoners died of hunger !

4 – The power and horror of the “Ditch”, a film banned in China:

The “Ditch” is the first fiction film by Wang Bing, known for his monumental documentary on the collapse of an industrial city in northeast China (“West of the rails”).

The shooting of this film, prepared by meetings with survivors, was totally illegal around the Mingshui camp where prisoners were transferred from Jiabiangou. The prisoners who lived in underground dormitories, cave-like, were digging a ditch which was later to irrigate the region.

A flat landscape and desert, wind, cold, hunger, the dead bodies which must be covered with sand every morning. The only objective is to survive, by ALL means.

A flat landscape and desert, wind, cold, hunger, the dead bodies which must be covered with sand every morning. The only objective is to survive, by ALL means.

The photography is beautiful and the music well adapted but the film with its strength and bluntness does not show the complexity of the short stories. The episode of the visit to the camp of the “Woman from Shanghai”, one of the most moving short stories, is a disappointing episode that fits poorly in the film.

But this film shows courage, it is a landmark and, hopefully will lead to read this short story collection of high quality.

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Yang Xianhui, “Woman from Shanghai, tales of survival from a Chinese Labor Camp”. Pantheon Books 2009, 300 pages.

(2) Yang Xianhui, ” Le chant des martyrs, dans les camps de la mort de la Chine de Mao” translated from the English by Patricia Barbe Girault, Balland, June 2010.

(3) Two books by Zhang Xianliang have been reprinted at Belfond: ” La mort est une habitude” ” La moitié de l’homme, c’est la femme”

Zhang Xianliang spent twenty years in various camps or prisons; notes from this period have been published in English: “Grass Soup” Minerva UK, 1994.

(4) Jean Pasqualini, “Prisonier de Mao”, Gallimard 1995.

(5) Harry Wu, ” Vents Amers” Bleu de Chine, 1995 and “Retour au Laogai,” Belfond 1996.

(6) Frank Dikötter, “Mao’s Great Famine,” Bloomberg 2010, 420 pages.