Feng Zikai (1898-1975) played an important role in the modern Chinese art scene. This is brought to our attention by “Color of Clouds” (1), a book that includes drawings and many of his essays and comments, translated for the first time and presented by Marie Laureillard-Wendland.

Feng Zikai (1898-1975) played an important role in the modern Chinese art scene. This is brought to our attention by “Color of Clouds” (1), a book that includes drawings and many of his essays and comments, translated for the first time and presented by Marie Laureillard-Wendland.

A very personal style, the “manhua”:

Born in Shimenwan in Zhejiang Province, a region that had suffered greatly from the Taiping rebellion, but which benefited later from silk production. His father finally succeeded in 1902 with the imperial examinations, but they will be abolished in 1905! In 1914 he became an intern at the Ecole Normale of Hangzhou where many celebrities have taught: Lu Xun, Zhu Ziqing, Ye Shentao. His music and art teacher, Li Shutong, who later became the monk Hongyi (1880-1942) will have a decisive influence on him both artistically and in the religious sphere.

At 22, he married, stopped studying and went to spend ten months in Japan where he learned more about Western painting and where he studied the works of the painter Takehisa Yumeiji.

To take care of his three children, he became professor near Shaoxing and began to publish his drawings in several reviews with the support of Zhou Zuoren (1885-1967) (2), Lu Xun’s brother.

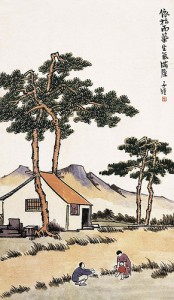

He called his drawings “manhua”, derived from the Japanese “manga” ; simple stroke, sophisticated composition, these drawings are in line with the taste of an audience sometimes weary of traditional painting. He supports the credo of Chinese painting “Outside, I take nature as a master, inside, I drink to the spring of my heart.”

He called his drawings “manhua”, derived from the Japanese “manga” ; simple stroke, sophisticated composition, these drawings are in line with the taste of an audience sometimes weary of traditional painting. He supports the credo of Chinese painting “Outside, I take nature as a master, inside, I drink to the spring of my heart.”

Painting and poetry:The painter must have a literary perspective because there are so many relationships between poetry and painting: “When I read poems about landscapes by the old masters, I often discover that they have an acute sense of perspective…It is obvious that painters and poets observe nature from the same point of view. ” This text, quoted by Geremie Barmé (3), professor at Canberra, in his excellent biography of Feng Zikai, is a key to understanding his work.

He is fairly isolated with his “manhuas” because in China, one prefers making use of traditional forms; the emphasis is on interpretation rather than on invention. But the sensibility of the artist is fundamental: to appreciate beauty is essential for a successful education and a happy life.The same goes for empathy: “the true artist must be in a total emotional communion with the object or person he depicts, sharing their joys and sorrows, their tears and their laughter. If you take the brush but you do not have a heart full of sympathy, you’ll never be a true artist “(3).

These qualities are also well represented in the texts of this book; the topics are very varied: personal and family recollections, street scenes, landscapes, social problems, Buddhist fervour. By cons, nothing here about painting which is dealt with in other essays, some of which are translated by Eric Janicot (4).

A remarkable text, “The outdoor hairdresser” (p. 132), demonstrates the links between life, drawing and the importance of composition. The style shows a great simplicity and controlled emotions, quite  different from the essays a bit unsettled and sometimes aggressive by Zhou Zuoren (2) or with a certain sentimental approach with Zhu Ziqing (5).

different from the essays a bit unsettled and sometimes aggressive by Zhou Zuoren (2) or with a certain sentimental approach with Zhu Ziqing (5).

The conversion to Buddhism:The year 1927 is that of all the misfortunes: massacres of leftist intellectuals ordered by Chiang Kai-shek moreover his mother and three of his children died. He goes through a moral crisis and he paints the portrait of an “old man of thirty years” in “Autumn” (1). At this moment he converted to Buddhism in front of his spiritual master Hongyi. He has no desire to become a monk, he is only interested in philosophy and not by rituals. In an essay “The Buddha does not help” (1), he rises against the followers who limit “Buddhism to a bargain, looking for a profit or personal gain.” “To reach the true faith, we must understand that all is vanity in this world, to refrain from any selfish attitude, experience the unity of self and others and show great compassion.”

Exile:The war made him leave Shanghai, then his house in Shimenwan which soon will be destroyed. He finally settled in Chongqing. He looks for a synthesis between traditional Chinese painting and the use of perspective, of light and shadows. He underlines “the superiority of Chinese art on that of the West by stressing that the respective assessments of the world are in opposition. Allusive, Chinese painting is in the order of spirituality.Western painting is related to empiricism. The first is spiritual, the second material “(4).

In 1943 he stopped teaching, his painting changed: he was painting figures in black and white, now, landscapes in larger sizes and in color; this is closer to public taste and allows him to exhibit and sell with success. He repeats himself, he copies himself, he becomes quite trivial and one may not be enthousiastic with his use of color.

In 1943 he stopped teaching, his painting changed: he was painting figures in black and white, now, landscapes in larger sizes and in color; this is closer to public taste and allows him to exhibit and sell with success. He repeats himself, he copies himself, he becomes quite trivial and one may not be enthousiastic with his use of color.

At the end of the civil war, he remains in China, while many Buddhist figures are leaving. He had violently criticized the Nationalist government and many of his close friends were Communists.

Soon, however, politics invades everything, drawings of “manhua ” style are used by the Party as propaganda instruments. As for himself, he is blamed for his bourgeois ideas about music and children literature. In 1952, he has to write a self-criticism; his support for the new regime brings him several official positions and a comfortable life. But he stopped painting and drawing, he translates several Russian or Japanese novels.

But he continues to work with the series of “Paintings to protect life” that he promised Hongyi to finish and he gets published in Singapore by a friend, the monk Guangqia.

He became an official artist and sometimes writes real propaganda texts. In 1966, he was challenged by posters and cartoons …! “Reactionary academic authority”, he is shown around with banners, he is locked up and writes many confessions. He was sent to farm in a village where he falls ill. In 1973, a formal investigation releases him; he leaves Shanghai for Hangzhou, where he died two years later.

His family home is rebuilt, it is now on the tourist tours of the province as well as that of Lu Xun and Zhou Zuoren in Shaoxing !

Bertrand Mialaret

(1) Feng Zikai, “Couleur de Nuage,” translated and introduced by Marie-Laureillard Wendland. Bleu de Chine-Gallimard 2010, 200 pages, 22 euros.

(2) Zhou Zuoren, “Selected Essays, translated by David E. Pollard. Bilingual edition. The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong 2006, 270 pages.

(3) Geremie Barme “An Artistic Exile, A Life of Feng Zikai” University of California Press 2002, 470 pages.

(4) Eric Janicot, “Fifty years of modern Chinese aesthetic.” Publications de la Sorbonne, 1997.

(5) Zhu Ziqing, “Traces”, translated and introduced by Lisa Schmitt. Bleu de Chine, 1998.

Very interesting article ! thanks for sharing with us. Thanks alot.