China is now the No. 1 worldwide for both the number of internet users and for mobile phones. Such an environment supported an extremely rapid development of literature on the internet. Creative writing, the role of publishers, the relationship between literature and other media, all that is doomed to change …

China is now the No. 1 worldwide for both the number of internet users and for mobile phones. Such an environment supported an extremely rapid development of literature on the internet. Creative writing, the role of publishers, the relationship between literature and other media, all that is doomed to change …

1 – China on the fast track:

China, with its 460 million Internet users has passed the United States; these users are young, they remain connected for a long time and have no reluctance to read books on screen. Cell phones (780 million) are used to access the net and to read books; reading on cell phone is developping fast even if we are far from the situation in Japan.

Nearly 30 million blogs; it is worth to mention that they accompanied the development of creative writing on the internet but did not create it. As for the economic environment, it is not, as in Europe, dominated by U.S. firms: the Google, Yahoo, Amazon, Ebay, are not leaders in China.

Finally, the electronic book industry is growing fast. The backlists are largely digital (not by Google!) and 40% of publishers simultaneously publish a text on paper and digital. Piracy is high and hinders the development of the market but the tradition was already well established with paper books!

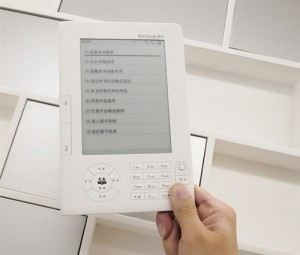

The player market (E reader) is limited (300,000 pieces during the third quarter 2011), which is low compared to sales of Kindle (Amazon) in the US.The two leaders of the Chinese market: Hanvon (60%) and Shanda, which launched its own reader (Bambook) with 20%. Competition is from smart phones, and also small portable PC’s and reading on cell phones. The entrance of Dang Dang on the market should develop the sale of E readers.

The player market (E reader) is limited (300,000 pieces during the third quarter 2011), which is low compared to sales of Kindle (Amazon) in the US.The two leaders of the Chinese market: Hanvon (60%) and Shanda, which launched its own reader (Bambook) with 20%. Competition is from smart phones, and also small portable PC’s and reading on cell phones. The entrance of Dang Dang on the market should develop the sale of E readers.

2 – Literature on the Internet, an example to follow?

The literature on the internet was born and grew outside traditional publishing.

The first literary websites were created in 1995. In 1997, was launched in Shanghai Rongshuxia.com which will become for some time the major player. From the year 2000, we see an enormous development: two main groups of readers / contributors, those who are less than twenty years old and the pensioned. Outside these two age groups, there is little time to read and write!

Volumes are staggering. Shanda, the group that bought the main sites (Qidian, the best known, Jinjiang and Hongxiu.com), totals 70 million unique visitors per month, a volume of 300 million pages per day. Qidian site is one of 30 most visited sites in China.

These writings are for entertainment, with an impact of various“fashions”: romance novels are still popular especially with women and recently the martial arts (wuxia) are somewhat in decline. Fantasy novels on the theme of tomb raiders, ghosts and vampire benefit from the popularity of novels such as “Harry Potter”.

For example, “A candle in the grave” by Zhang Muye, a fantasy novel written in a year during his leisure time, by a financial executive, will generate six million contacts.

This also limits the risks for publishing: success on the Internet brings the sale of 600,000 copies and a movie followed. The site Qidian published 500 titles for a total of 30 million copies.

3 – Competition and “star system”.

Competition is severe, managers, and authors easily change site. Lu Jinbo, an author on the net, became a star of the marketing of sites and publishes writers as famous as Wang Shuo and Han Han.

The general portals such as Sina and Sohu are now competing with literary sites, not only because they sell Ebooks on line, but especially with the development of their own authors under contract.

The main difficulty is to keep readers, positions are never stable. This means that you have to create events. The award in 2002 of the Lao She Literary prize to Ning Ken, an author published only on the net, came as a shock.

A new generation of writers started on the web, they are young and very concerned about their “look”, they often fill the columns of the popular press with their love affairs or lifestyle (Han Han is also a race car driver!)

A new generation of writers started on the web, they are young and very concerned about their “look”, they often fill the columns of the popular press with their love affairs or lifestyle (Han Han is also a race car driver!)

4 – Are multimedia companies a chance for literature?

Success depends primarily on the members, contributors and readers. The contributor provides a text which if selected, can be brought online. Some authors are under contract (4000 with Qidian). The first half of the text can be read free of charge and then 3 yuans for 100 000 characters (a very small amount to try to fight against piracy); this income is split 50/50 between the site and the author.The authors are kept under contract but in fact motivated to increase the number of pages which is not always a guarantee of quality.

Qidian has 150,000 contributors, but some authors become writing “convicts”: Zu Hongzhi is a 22 years old student who dropped out of Suzhou university, his nickname is “I like eating tomatoes!” Like ten other authors, he earned more than 100 000 euros per year, but had to produce 10 million words of martial arts novels in the last four years!

But for the author under contract with Qidian, the primary goal is certainly to have readers but not to be published in book form and this is a fundamental change. Also with the Internet, it is not an elite but the largest number that decides on the quality of a text.

The literary sites on the Internet have developed many services for their members, often in partnership with third parties. Other media have been included: radio, trading of rights for TV and film adaptations and especially for video games.

75% of revenues (approximately $ 280 millions) of the parent company of Qidian (the Chinese company Shanda Interactive Entertainment, publicly listed in the U.S.) comes from video games and especially the popular role-game networks. This may enhance the development of Qidian towards works of fantasy and “fantasy” that can be the source of new video games.

However efforts are being made to improve the quality of contributions: Qidian funded the training of 1 000 contributors with creative writing courses with the Academy of Social Sciences of Shanghai.

Some think that these literary sites are freedom areas. Probably not when you look at censorship and especially self-censorship towards sensitive issues. The idea is to entertain and not to ask too many questions, no excessive violence, pornography or “negative political trends.”

This is why some (Mo Yan, Wang Anyi), famous long before the web, think it’s just a fad, but there is a risk that the literature that has survived with difficulty the Maoist period, may suffer from these developments. Others have mixed feelings: Yu Hua has agreed to several chapters of “Brothers” to be freely available on the net and has just published a selection of articles from his blog only in digital form. Shanda has already hired, as a consultant Wang Meng, a former minister of culture who headed the Chinese delegation to the Frankfurt Book Fair.

This is why some (Mo Yan, Wang Anyi), famous long before the web, think it’s just a fad, but there is a risk that the literature that has survived with difficulty the Maoist period, may suffer from these developments. Others have mixed feelings: Yu Hua has agreed to several chapters of “Brothers” to be freely available on the net and has just published a selection of articles from his blog only in digital form. Shanda has already hired, as a consultant Wang Meng, a former minister of culture who headed the Chinese delegation to the Frankfurt Book Fair.

Bertrand Mialaret